Bangkok (Thailand), 3 May 2024 – “I left Myanmar because I felt unsafe.”

Ibrahim*, a Rohingya man in his twenties, said armed conflicts and intentional burnings of his village had “forced everyone to flee.”

He’s not the only one. New research from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) found that tens of thousands of people from Myanmar, other parts of Southeast Asia, and from outside the region are smuggled to, through and from Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand every year.

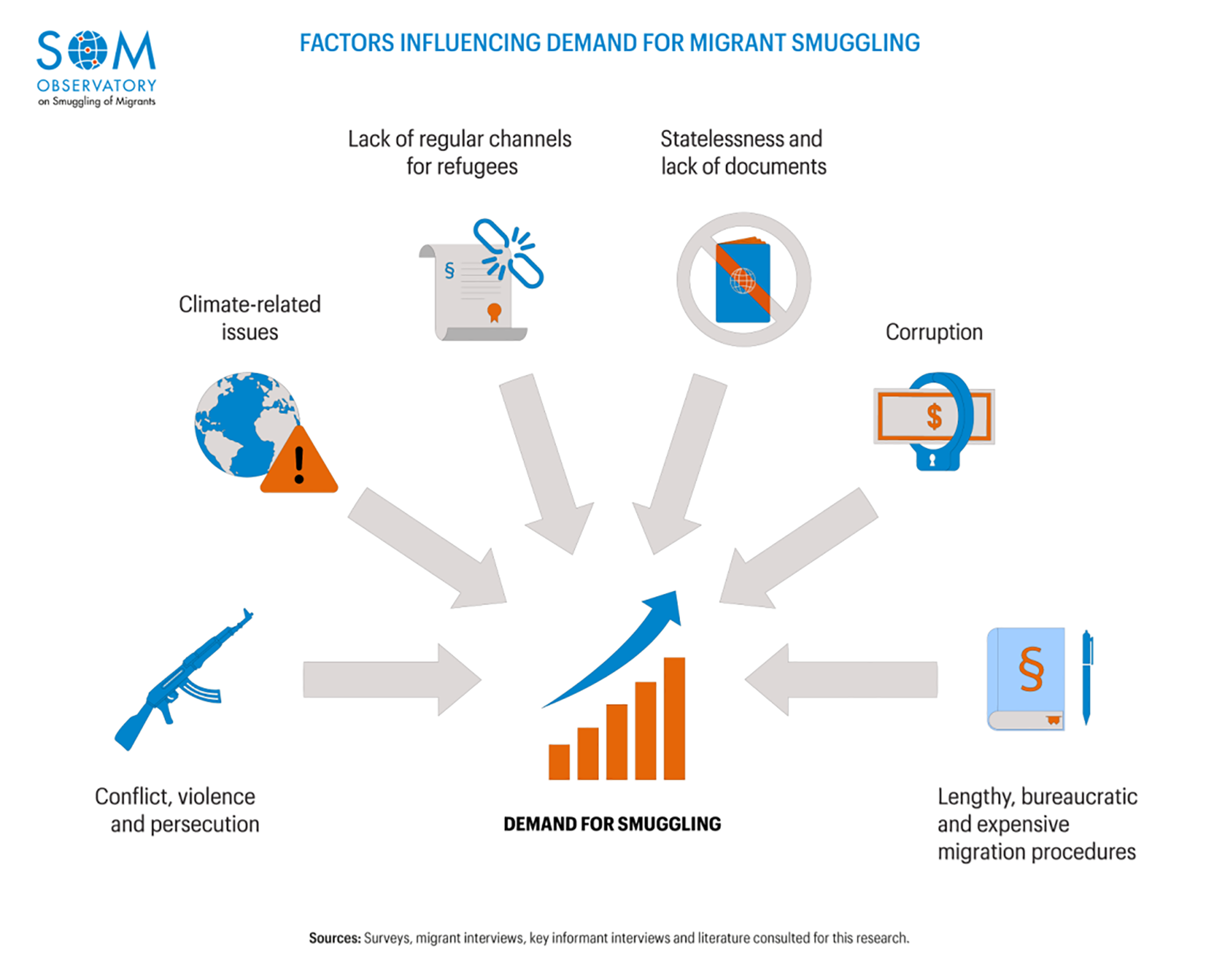

The study Migrant Smuggling in Southeast Asia, the latest research to be published by UNODC’s Observatory on Smuggling of Migrants, finds that persecution, statelessness, a lack of legal channels for asylum and labour migration, and corruption are the primary drivers of the demand for smuggling services.

“Demand is massive in terms of people needing to flee awful circumstances, needing to flee conflict, particularly out of Myanmar,” said one informant interviewed for the research in Thailand. “And then the lack of legal pathways to get to where they need to go just culminates in a perfect storm for the need for smuggling services.”

The research demonstrates that demand for smuggling is driven by various and often complex factors — and arises among refugees and migrants because they perceive a lack of alternatives for regular migration. Some, like Ibrahim, are fleeing conflict, violence and persecution.

Others, like Indah*, an Indonesian woman in her mid-forties, feel they have limited access to regular channels for labour migration.

“My friends also told me that the chance of getting into Malaysia is lower if we come on our own,” she reported. “Some people get rejected at immigration if they don’t use a tekong [smuggler], because the tekong pays a bribe to the immigration authorities, which they call ’guarantee money’”.

Still other would-be migrants and refugees are stateless or lack travel or identity documents.

“I did not have travel documents,” said one Chin woman from Myanmar. “I just came here with the help of the agent [smuggler]. We never applied for documents because the soldiers were everywhere in the country, even at the airport.”

Corruption both enables and drives smuggling, the research shows. 25% of smuggled people surveyed reported giving officials a gift, money, or a favour in order to obtain a service. Corruption also drives demand for migrant smuggling, with smuggled people perceiving that they need smugglers to help them deal with corrupt authorities.

“The services provided by the tekong included transport, food, accommodation in a hotel, passport and ‘guarantee money’ to the immigration authorities,” Indah added.

Smuggling fees per person range from 100s to 1,000s of US dollars, depending on the mode of smuggling — land, sea, air or a combination — and are usually paid in cash, so the amounts are rarely traceable.

Regardless of the reason behind their migration journeys, most of the 4,785 migrants and refugees surveyed for the research — 75% — experienced some form of abuse en route.

“Agents are meant to abuse you,” said one Rohingya man. “That is the law by which agents live.”

65% of smuggled migrants and refugees experienced physical abuse perpetrated by the military, police, smugglers, border guards or criminal gangs. 11% of women and 6 % of men experienced sexual abuse, while 9% of men and 6% of women witnessed deaths.

“The journey was scary,” admitted Lian*, a 19-year-old Chin man from Myanmar describing his eight-day journey from Yangon to Kuala Lumpur. “We only travelled at night. We couldn’t use any lights and were just following the person in front of us without knowing what was going to happen. Sometimes, people would get lost.”

“It was very difficult for me to survive in the mountains,” agreed Aung*, a 19-year-old woman from Myanmar recounting her journey to Thailand. “I heard some gunshots, and there were rumours about the authorities searching for illegal border crossers. Even though I was resourceful, I still faced difficulties in finding enough food and water. Climbing the mountains was also very challenging; it was scary because there was a risk of falling.”

Yet almost half (48%) of smuggled migrants and refugees surveyed said that they would have taken the journey anyway, knowing what they did now about the conditions; 40% said they would not have, while 12% were undecided.

This is a testament to the intensity of the demand for migrant smuggling in the region, the determination to travel at all costs — and the profits that can be made from this illicit industry.

The full research study, including interactive and static maps and graphs, infographics, case studies and research methodology, can be accessed here. The Observatory is UNODC’s principal knowledge source to develop the evidence base on smuggling of migrants, as a service to Member States to inform their counter-smuggling responses to combat the crime of smuggling of migrants and to protect the rights of smuggled migrants.

*Name changed to protect privacy