Playing fair on and off the sports fields

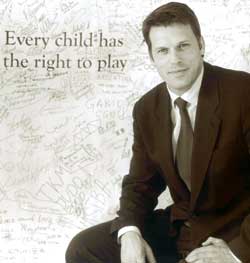

Johann Olav Koss, four-time Olympic gold medallist in speed skating, is now the President and Chief Executive Officer of the NGO Right to Play. This organization, which grew out of the 1994 Lillehammer Olympic Aid initiative, uses sport and play for the development of children and young people. Koss has also been involved in a range of anti-doping initiatives, both before and after his retirement from competitive sport.

By Raggie Johansen

Koss does not believe more athletes are cheating now than when he was active in the mid-1990s. In his opinion, there is in fact less doping in sport than most people believe.

Koss does not believe more athletes are cheating now than when he was active in the mid-1990s. In his opinion, there is in fact less doping in sport than most people believe.

"I think the level of cheating is quite constant," he says, "But some sports are more tainted than others, and we need an even stronger focus on the problem. I don't know if it's possible to win this game, because it's tough to combat all cheating in sport."

Profit is a key reason for doping, according to Koss. People close to the athletes, often coaches or other team leaders, try to influence them to use performance-enhancing drugs that will help to increase their earnings.

"These people are using the athletes' potential for fame and money," he says. "I don't think athletes would normally say 'I want to use drugs.'"

Koss believes athletes should be banned for life once caught using illegal substances. Furthermore, he suggests long-time storage of blood and urine samples for possible future drug detection when the technology is more advanced.

Athletes might be deterred from using drugs if they knew that although it is not possible to detect a particular substance today, it might be possible three or four years down the road, using the stored samples. If so, the athletes would lose their medals and their glory retroactively.

Despite the problem of doping, Koss continues to believe that sport has the power to bring out the best in professional athletes, many of whom are eager to contribute to and get involved with the work of Right to Play. He cites the example of the American speed skater and Olympic champion Joey Cheek, who not only donated his prize money to Right to Play but also highlighted the plight of children in Darfur at a press conference.

Through Right to Play, athletes can help build a bridge between sport and development in some of the most disadvantaged areas of the world, Koss says. Sport is not only about having fun, it also brings people together and strengthens local communities.

Young people who participate in sport learn about rules, teamwork and fair play, which in turn can lead to democratic decision-making in their communities. Playing sport together often also inspires young people to undertake joint activities for the common good, such as building playgrounds and sports fields. In addition to appreciating the broader community benefits, Koss is also clearly inspired by the direct, tangible impact his organization's work can have on individuals. He tells the story of one Right to Play coach in the Lugufu refugee camp in Tanzania: "This guy is young, probably about 21-22 years old. And he really is a Right to Play coach-it's his life, his inspiration and what he loves to do. Every day, he gets hundreds of kids involved in activities. He got married in the refugee camp and has two children. And because of his work, he chose to name them after international Right to Play volunteers. It's really incredible to see the impact we have had on him."

Young people who participate in sport learn about rules, teamwork and fair play, which in turn can lead to democratic decision-making in their communities. Playing sport together often also inspires young people to undertake joint activities for the common good, such as building playgrounds and sports fields. In addition to appreciating the broader community benefits, Koss is also clearly inspired by the direct, tangible impact his organization's work can have on individuals. He tells the story of one Right to Play coach in the Lugufu refugee camp in Tanzania: "This guy is young, probably about 21-22 years old. And he really is a Right to Play coach-it's his life, his inspiration and what he loves to do. Every day, he gets hundreds of kids involved in activities. He got married in the refugee camp and has two children. And because of his work, he chose to name them after international Right to Play volunteers. It's really incredible to see the impact we have had on him."

The joy and excitement of sport can also serve as a powerful incentive for people to do things they might otherwise be reluctant to do. In Zambia, for example, Right to Play arranged a football tournament on fields next to a vaccination site, and created a "trading card" with a picture of local soccer star Kalusha Bwalya. As a result, the number of vaccinations increased dramatically.

Right to Play is working alongside various United Nations agencies, private sector groups and sport federations in an international working group to promote sport as a tool to achieve development and peace. The aim is to give sport more prominence in national policies."

Governments don't take physical activity seriously any longer," Koss says. "But, since sport is linked closely to the Millennium Development Goals, we have managed to develop a cross-sectional approach where all relevant ministries receive advice on how to integrate sport in their work."