South Africa: Two hours in Pretoria Central

By Raggie Johansen

I pass through the gates of Pretoria Central Prison on a warm, sunny day. I've come to learn more about prisoner rehabilitation work undertaken by Khulisa, a South African NGO working in partnership with UNODC, which trains inmates to become peer drug and HIV counsellors. The programme I am about to observe runs over six months, with sessions once a week.

Security at the prison's Medium C block is tight and I wonder what it must be like at Maximum Security. I pass through a metal detector, am briskly patted down and I have to hand in my camera, my handbag and my UN passport for safekeeping at the entrance gate. All I am allowed to keep is my notebook and pen.

After passing a massive wooden gate and a floor-to-ceiling metal turnstile, where two separate prison warders have to press buttons to allow entry, I see a large, sparse room where approximately 35 prisoners are seated in an oval. They are all wearing uniforms; bright orange for men, dark blue for women. These people are serving long sentences for offences like murder, rape and assault. Most of them are in their twenties but some appear to be in their late forties. I am surprised to see around 15 women in the group as women account for less than three per cent of South Africa's total prison population.

Thabo Morake, the facilitator from Khulisa, introduces me, and the session continues. The discussion, while relatively loose and informal, centres on issues of negative behaviour and how inmates can bring about lasting change in themselves as well as within peer groups.

"I want to live a healthy life and lead by example," says one man, gesticulating eagerly as he speaks. "We can't actually change other people, we can only try to guide them."

I am surprised at the way this group interacts. Although there are wide differences in gender, age, colour and religion, the atmosphere is one of mutual respect, humour and inclusiveness. People feel comfortable speaking freely about deeply personal issues and they do so with great enthusiasm and eloquence.

"You know, mister Thabo, I used to smuggle, sell and smoke a lot of dagga (cannabis)," says one inmate, wearing an oversized red sweatshirt on top of his orange prison overall. "Now I've realized that it was wrong, that I was spreading a lot of negative energy. I have to change, and as a peer counsellor, I will."

Although the eagerness to change for the better is evident in most participants, they are not naïve. They know full well that many of their fellow inmates are less than receptive to the idea of giving up drugs. "They (other inmates) will kill us if we go out there and tell them to stop," one man said.

But most participants seem to take pride in the training they are receiving, and they want to be successful as peer counsellors. They speak of how the training has boosted their confidence and how they have uncovered talents they never knew they possessed. Their homework assignments include designing a poster about different types of drugs together with a fellow inmate who is not a course participant, so they get real-life practice in educating peers about drugs.

The session I sat in on also covered relations with family members. I expected to hear tales of anger, grief, loneliness and rejection. In fact, most of those who spoke actually reported an improvement in relations.

"My family relationships are stronger now," one woman said. "From inside, I can appreciate that my mum is taking care of my child. And I don't have to see my mother as often as before, which is easier."

A man in his late twenties says that his parents never used to know what he was up to before he was imprisoned. He says he never told his parents he loved them and kept contact to a minimum. However, from prison, he calls his mother every morning. He says he is very happy that his parents keep visiting him and that they don't judge him for the mistakes he has made.

I am conscious that this is a highly select and motivated group of inmates. There are many thousands who will never receive, or even want, this training opportunity. But at the same time, just knowing that it is possible for people in the unlikely setting of a prison to willingly undergo profound personal change is very encouraging.

"Hey, didn't you say you're a journalist?" one inmate asks me, with a broad smile on his face as Thabo closes the session. "Please go out there and tell the world that South Africa is not only about crime and bad things. There are many of us who want to change and make this country a better place to live."

On my way out, I stop the only participant who is wearing civilian clothes. I ask her why. She says she was released from prison several weeks ago, but she enjoys the programme so much that she keeps coming back.

"I've learned a lot and it would be a pity to quit now," she says. "In fact, I want to be like Thabo and work with prisoners myself one day."

This training has had a positive impact on the lives of many prisoners, who end their sentences not simply as trained drug and HIV peer counsellors, but also with increased confidence and motivation to help others change their lives. UNODC plans to extend the training and peer counselling to benefit an additional 7,000 prisoners.

|

|

|

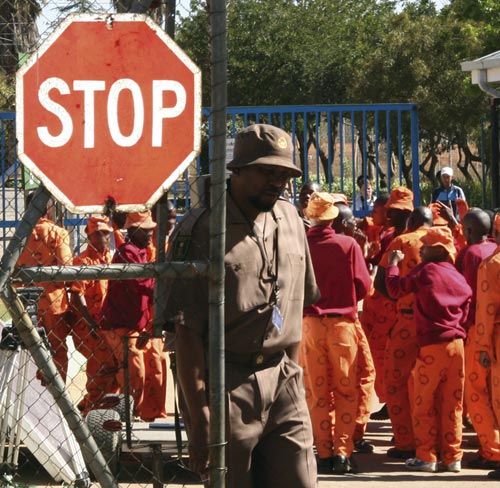

UNODC works with the South African authorities and NGOs to help reduce drug abuse and HIV/AIDS in prisons. This photo shows Leeuwkop prison near Johannesburg |