Somebody has to do it, why not me? - The story of a female prison officer from Kazakhstan

Achieving gender equality and the empowerment of women (GEEW) is integral to each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Gender equality and women’s empowerment is not only a specific SDG (SDG 5) but also considered a cross-cutting theme that affects the achievement of all other SDGs.

Gender-sensitive techniques should be adopted in recruitment, retention and promotion of women in prison administrations to correct any gender imbalance. Women staff should be recruited and trained to work with women violent extremist prisoners and design and deliver gender-appropriate interventions. Prison officers working with violent extremist prisoners require a good combination of personal qualities and technical skills. They need personal qualities that enable them to deal with all prisoners, including the difficult, dangerous and manipulative, in an even-handed, humane and just manner.

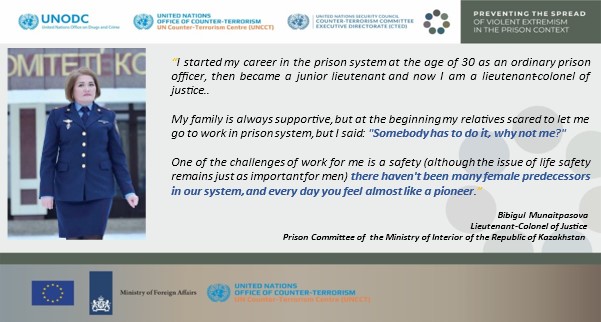

Bibigul Munaitpasova, the Head of the Department for Educational and Socio-psychological work with prisoners of the Prison Committee of Kazakhstan, has come a long way in her career: she worked as a psychologist, as a squad head, an inspector for labor organization in prison, as a chief specialist on educational and socio-psychological work among prisoners within the department. Then she took up a senior position in a female prison as a Deputy Head of the prison, responsible for educational and socio-psychological work. Now she is a Head of Department in the headquarters of the Prison Committee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kazakhstan. Her work experience across various levels of the prison system gives her an in-depth knowledge of all the practical aspects of the prison system, and this helps her to cope successfully with her duties.

Bibigul believes that a person should follow their passions.

"I enjoy my work and feel the responsibility and need to pass on my experience to younger prison officers," she says.

"My family is always supportive but at the beginning my relatives scared to let me go to work in prison system, but I said: "Somebody has to do it, why not me?" Now they understand and respect my choice. This is a great credit to my father, who always said: "Daughter, life is yours, do what gives you pleasure." This is the maxim I follow. One of the challenges of work for me is safety, for example, when working in a maximum-security prison facility (although the issue of life safety remains just as important for men). In addition, there haven't been many female predecessors in our system, and every day you feel almost like a pioneer," says Bibigul.

"When the pandemic began, I worked in a female prison, and the enormous burden of responsibility for the health of those serving their sentences was the greatest challenge. It was encouraging to see that every prison officer felt this responsibility and that sanitary and hygienic norms were carefully followed, which helped to prevent illness and protect prisoners. One of the advantages of the innovations that came with the pandemic is that online working, using video conferencing, is intensively entering our daily activities. The online format means there is no need for passes and other formalities, it has become much easier to organize various kinds of educational activities within the prison facilities. Today we are increasingly using video lectures for inmates," Bibigul says.

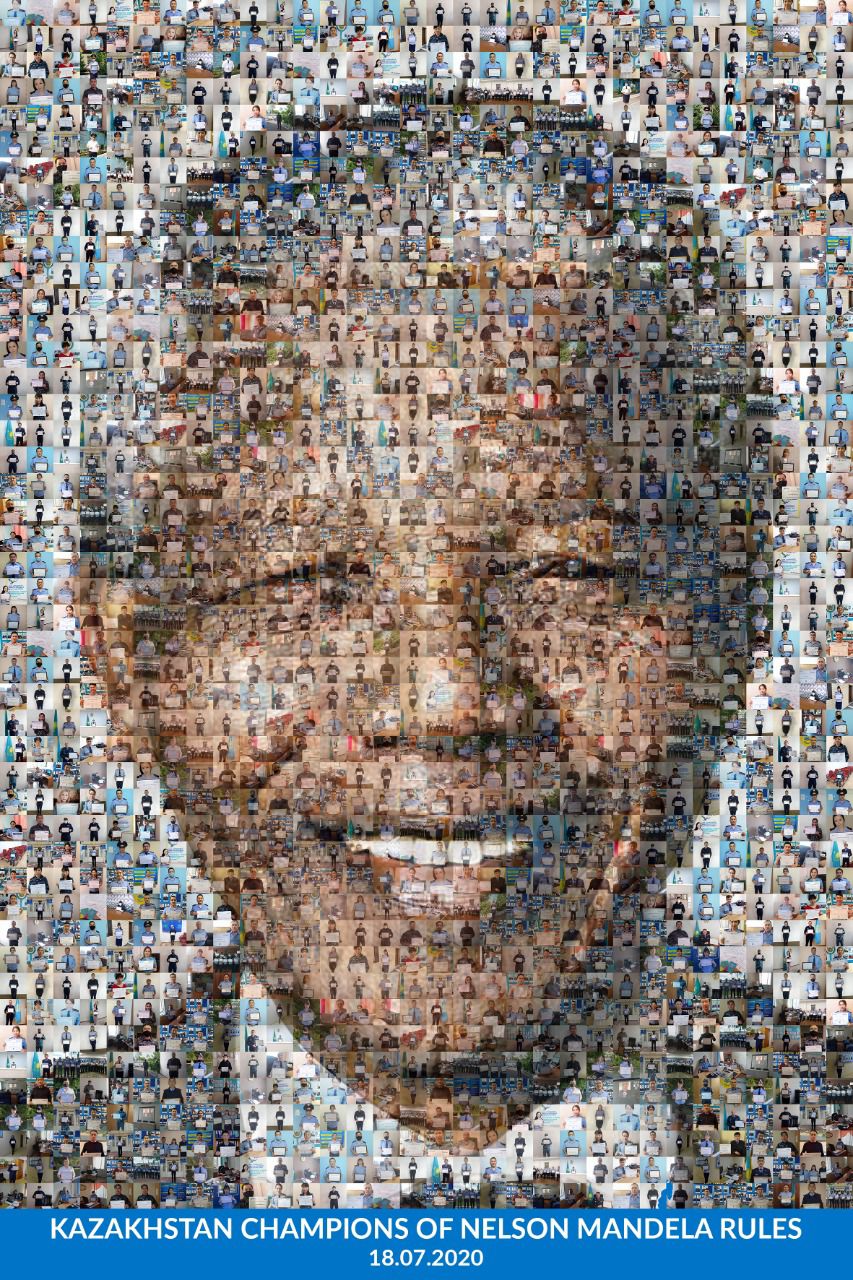

‘’32% female prison officers successfully completed the UNODC-supported e-learning course on the Nelson Mandela Rules’’

In 2020, the Kostanay Police Academy of Kazakhstan rolled out the UNODC-supported e-learning course on the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners – the ‘Nelson Mandela Rules’ among prison and probation officers. To date, over 2,500 (32% female) prison officers have taken the e-learning course to better understand and apply the Nelson Mandela Rules as the universally acknowledged minimum standards for the treatment of prisoners. Dissemination of the e-learning course on the Nelson Mandela Rules was combined with in-service trainings on specific topics, such as the management of violent extremist prisoners and prevention of radicalization to violence in prisons.

"This is very useful work, which helps to share knowledge on the international standards for the treatment of prisoners, improve conditions in institutions and motivates prison officers to improve their skills," says Bibigul.

"I can note many positive changes in my practice as a result of the online courses on the Nelson Mandela Rules at the legislative level. Respectful treatment with prisoners on a mandatory basis; introduction of the electronic system of appeals/requests; reduction of time spent in solitary confinement; implementation of cell-based confinement practice in eight penitentiary institutions of Kazakhstan, as well as increasing the norms of individual living space for prisoners. Most importantly, this course was relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic, when traditional forms of training for prison staff were rapidly transferred to an online format."

Among her short-term plans, Bibigul mentions the development of new prison-based rehabilitation programmes for violent extremist prisoners, based on new individual risks and needs assessment system. The results of the risks and needs assessment will allow prison officers to develop an individualized sentence planning, taking into account needs for further rehabilitation and social reintegration upon release.

"Within the framework of the joint EU - UN Programme, activities are underway to improve the professional qualifications of three categories of prison staff, i.e. prison psychologists, prison security officers, and PVE inspectors. They are that very "main nexus" in working with violent extremist prisoners.

Eight pilot prisons with different security levels (reaching out over 100 violent extremist prisoners), ranging from low to maximum security levels, including a female prison are participating in the joint EU-UN programme. The prison officers in the pilot prison facilities passed the necessary in-service training, and working conditions were improved by renovating and equipping prison facilities. But it is also important to note that vocational training classes for prisoners in the pilot prison facilities were also supplied with equipment to create employment opportunities for prisoners, both within the prison and after release," says Bibigul.

"Even though I am comparatively new in my current position, I would like to note that the work carried out by the joint EU-UN joint programme ‘on management of violent extremist prisoners and prevention of radicalization to violence in prisons’, especially related to prison staff training, is already yielding results, for which I express great gratitude on behalf of the Prison Committee to UN organizations and donors."

Capacity development of prison officers in Kazakhstan is supported within the framework of the joint EU-UN global initiative “Supporting the Management of Violent Extremist Prisoners and the Prevention of Radicalization to Violence in Prisons” implemented by the UNODC, UNCCT in partnership with the UNCTED with financial support from the European Union, the UNOCT and the Government of Netherlands.

This story in Russian language

For further information, please contact:

Sultan Khudaibergenov

Communication and External Relations Officer

UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia

Email: sultan.khudaibergenov[at]un.org