This module is a resource for lecturers

Topic four - Justice for children in conflict with the law

The material presented in the previous topics is also relevant to children involved in justice proceedings, including children alleged as, accused of or recognized as having infringed the penal law (children in conflict with the law). In addition, however, it is important to consider the specific legal provisions, within the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) that pertain to the administration of juvenile justice (notably, articles 37 and 40).

International legal safeguards for children in conflict with the law: The Convention on the Rights of the Child

Article 37

States parties shall ensure that:

(a) No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without possibility of release shall be imposed for offences committed by persons below eighteen years of age;

(b) No child shall be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily. The arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time;

(c) Every child deprived of liberty shall be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, and in a manner which takes into account the needs of persons of his or her age. In particular, every child deprived of liberty shall be separated from adults unless it is considered in the child's best interest not to do so and shall have the right to maintain contact with his or her family through correspondence and visits, save in exceptional circumstances;

(d) Every child deprived of his or her liberty shall have the right to prompt access to legal and other appropriate assistance, as well as the right to challenge the legality of the deprivation of his or her liberty before a court or other competent, independent and impartial authority, and to a prompt decision on any such action.

Article 40

1. States parties recognize the right of every child alleged as, accused of, or recognized as having infringed the penal law to be treated in a manner consistent with the promotion of the child's sense of dignity and worth, which reinforces the child's respect for the human rights and fundamental freedoms of others and which takes into account the child's age and the desirability of promoting the child's reintegration and the child's assuming a constructive role in society.

2. To this end, and having regard to the relevant provisions of international instruments, States parties shall, in particular, ensure that:

(a) No child shall be alleged as, be accused of, or recognized as having infringed the penal law by reason of acts or omissions that were not prohibited by national or international law at the time they were committed;

(b) Every child alleged as or accused of having infringed the penal law has at least the following guarantees:

(i) To be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law;

(ii) To be informed promptly and directly of the charges against him or her, and, if appropriate, through his or her parents or legal guardians, and to have legal or other appropriate assistance in the preparation and presentation of his or her defence;

(iii) To have the matter determined without delay by a competent, independent and impartial authority or judicial body in a fair hearing according to law, in the presence of legal or other appropriate assistance and, unless it is considered not to be in the best interest of the child, in particular, taking into account his or her age or situation, his or her parents or legal guardians;

(iv) Not to be compelled to give testimony or to confess guilt; to examine or have examined adverse witnesses and to obtain the participation and examination of witnesses on his or her behalf under conditions of equality;

(v) If considered to have infringed the penal law, to have this decision and any measures imposed in consequence thereof reviewed by a higher competent, independent and impartial authority or judicial body according to law;

(vi) To have the free assistance of an interpreter if the child cannot understand or speak the language used;

(vii) To have his or her privacy fully respected at all stages of the proceedings.

3. States parties shall seek to promote the establishment of laws, procedures, authorities and institutions specifically applicable to children alleged as, accused of, or recognized as having infringed the penal law, and, in particular:

(a) The establishment of a minimum age below which children shall be presumed not to have the capacity to infringe the penal law;

(b) Whenever appropriate and desirable, measures for dealing with such children without resorting to judicial proceedings, providing that human rights and legal safeguards are fully respected.

4. A variety of dispositions, such as care, guidance and supervision orders; counselling; probation; foster care; education and vocational training programmes and other alternatives to institutional care shall be available to ensure that children are dealt with in a manner appropriate to their well-being and proportionate both to their circumstances and the offence.

These legally binding obligations on States are elaborated further in the internationally authoritative rules and minimum standards detailed in the United Nations standards and norms on juvenile justice (as listed in Topic Three of this Module).

Underpinned by the fundamental human rights principle of respect for human dignity, these important legal safeguards illustrate that effective justice responses for children require individualized responses that recognize the specificities of a child’s circumstances, including their age. Yet these articles do not apply in isolation - children in conflict with the law are, after all, children, to whom the full range of children’s rights apply. The Committee on the Rights of the Child affirms the interdependence and indivisibility of children’s rights in both General Comment No. 10, on Children’s Rights in Juvenile Justice (2007), and General Comment No. 24 on children’s rights in the child justice system (2019). These General Comments, which are set as core reading for this Module, detail the expectation that States parties develop a comprehensive approach to juvenile justice, in which the provisions of articles 37 and 40 are implemented, but which also take into account the general principles in all other relevant articles of the CRC. This means that the obligation rests with States parties to ensure not only that children are free from arbitrary and unlawful detention, but also that children’s rights to health, education, artistic and leisure activity are upheld. This applies to all children, without discrimination, and the CRC is clear that this obligation extends to social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies.

Understanding the root causes that bring children into conflict with the law

Children in conflict with the law are often those who face multiple and intersecting challenges in their lives. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) confirms the multiplicity of risks that bring children into conflict with the law, and the importance of multi-sectoral responses that are tailored to a child’s individual circumstances.

[M]ost young people who come into conflict with the law are struggling with multiple social and economic issues in their homes and/or communities. These issues range from being on the streets as a result of poverty and/or family dysfunction to coping with peer pressure in relation to risk-taking such as minor theft and substance abuse. Interventions need to be holistic to achieve maximum sustainable impacts. They must recognize the root causes of a child’s criminal behaviour and identify appropriate services to help the young person address the problems. Services needed may include support for basic education and skill training, employment, drug rehabilitation and family counselling (UNICEF, 2004 p. 102).

The following example illustrates the importance of a comprehensive an integrated approach to justice for children.

Example: A comprehensive approach to access to justice

Sam, who lives with his mother and father, has been witness to extreme violence between his parents since he was four years of age. By the time Sam is 11-years-old, his parents’ have decided to dissolve their marriage, and they have become embroiled in complex divorce proceedings in the Family Court. On review of the history of extreme violence, and parental substance abuse, the Court decides that Sam should be removed from his parents and placed in alternative care. The location of Sam’s accommodation unit requires that he change schools. This means that in addition to losing daily contact with his parents, Sam also loses his friends, his teachers, and his soccer team. Sam makes a new friend in the accommodation unit and, together, they start skipping school, consuming alcohol, and breaking into cars to steal. Eventually, the manager of the accommodation unit observes this behaviour, and reports Sam and his new friend to the police. Sam is charged with breaking and entering a motor vehicle and, given he is above the age of criminal responsibility in his country, he faces criminal sanction for his actions.

Sam’s situation is extremely complex, and “justice” would involve much more than ensuring that he has access to a defence lawyer to assist with proceedings for the criminal charge. The rights enumerated in the CRC, and the authoritative guidance elaborated in the relevant UN standards and norms on crime prevention and criminal justice, provide a strong foundation for understanding what a concept of “justice” would encompass for Sam.

Deficiencies in child protection systems

Vast numbers of children become enmeshed in criminal justice systems due to shortfalls in welfare and social service response. In many jurisdictions, when children from adverse circumstances come into conflict with the law, they can be held in closed facilities as a putative welfare measure, even when the child’s actions do not constitute a substantive breach of the penal law. Various euphemistic terms are used to describe “protective custody” or “secure welfare” and, in many instances, children accused of breaching the law are held on remand simply because they lack the support and supervision necessary to satisfy bail conditions. In instances where family, community, or social services fail to provide children with the level of support they require, the justice system can step into the breach.

The criminal justice system is still used in many countries as a substitute for weak or incipient child protection institutions, generating approaches that further stigmatize socially excluded children, including those who have fled home as a result of violence or neglect, those who have been abandoned, and are homeless or poor, at times living or working on the street; and also those who suffer from mental health or substance abuse problems. (Santos Pais, 2015, p. 19).

Depending on the jurisdiction, the provisions for detaining children for their own “protection” are found in juvenile justice legislation, child protection statute, or, decisions of this kind are operationalized through the discretion of police, judicial officials, and parole boards. Irrespective of whether the custodial term is framed as a justice decision or a protective measure the outcome is that children are held against their will and, in most cases, the institution in which the child is detained fails to provide the protective socio-ecology required for a child’s developmental well-being. The regularity with which this occurs, globally, reflects poorly on those charged with the care of children (whether parents, the State, or contracted carers) and it raises extremely confronting questions about the value that children hold in society more generally. The section that follows traces just some of the contexts in which children can be criminalized due to deficiencies in child protection systems; or discriminatory or punitive law and procedure.

Survival crimes and the link to child exploitation

When children breach the law in order to survive, formal contact with the criminal justice system is likely to deepen and prolong a child’s socio-economic exclusion. Acts of survival for which children may be criminalized include begging, theft, drug offences, and sex work (Anti-Slavery International, no date). A child-sensitive and rights-based approach precludes the attribution of criminal culpability, both on the basis of the principle that children be diverted from formal criminal justice involvement wherever possible, and because of the profound vulnerability of children engaging in survival crimes (including children who are trafficked or otherwise forced to engage in crime). The following excerpt describes the hardship that compels children to engage in “survival sex” in South Asia:

Children surviving on the streets alone, with their families or linked to the establishment where they work are more frequently found in large-sized South Asian cities. Homeless and disenfranchised, they lack basic care and may trade protection in exchange for favours, especially when they spend the night in the open on pavements, or in makeshift accommodations in squatter colonies, on footpaths, on railway platforms, at bus stations, below flyovers, at unprotected construction sites or workplaces. Survival sex is a frequent coping mechanism to procure food, drugs and entertainment opportunities. (ECPAT, 2017, p. 59).

Despite the complex contexts which give rise to these forms of child exploitation, the risk of criminalization, in all regions, compounds the harm for children forced to engage in survival crime. The sexual exploitation of children is a field in which there has been particular recognition of children as exploited victims of child sex abuse, rather than culpable criminal actors (see, for example, Phoenix, 2016).

Example: Structural challenges in Angola create risks to child sexual exploitation

The supplementary report to the periodic reports of Angola, on the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child regarding sexual exploitation of children, identified that the persistence of all forms of sexual exploitation of children constitutes a “grave” problem in Angola. Jointly drafted by non-governmental organizations working to combat the sexual exploitation of children (SEC), the supplementary report identifies the following structural factors perpetuate SEC.

With over 13 million of children, more than half of Angola’s population is below the age of 18. Only 36% of children are registered at birth. Unregistered children are more vulnerable to trafficking, sexual exploitation, child marriage and child labour. (OMUNGA Association, et al, 2018, p. 3.)

The main causes of SEC are poverty, unemployment, unstable families, AIDS/HIV pandemic, parental disengagement and lack of access to education and basic social services. Other relevant factors are social tolerance and demand for sex with children and the risks posed for children living or working in the streets. (OMUNGA Association, et al, 2018. p. 4)

In response to these challenges, the supplementary report identifies a range of measures necessary to prevent and prohibit SEC, and to protect the rights of child victims.

Source: OMUNGA Association et al, 2018.

Notwithstanding the global attention to the plight of sexually exploited children, and the concomitant refusal that such children be seen as ever being able to voluntarily engaging in “sex work”, safeguards are required in all jurisdictions to prevent the criminalization of sexually exploited children, and to ensure that children receive child sensitive and victim-oriented responses (Phoenix, 2016). Among the children at risk of criminalization for acts necessary for their survival are unaccompanied or separated children in cross-border situations, or contexts of migration (Achilli et al, 2017). Where children are trafficked for the purposes of engaging in begging, or a range of crimes including ATM theft and cannabis cultivation, safeguards are required to ensure that children are identified as victims of crime, rather than independent and culpable criminal agents (Anti-Slavery International 2014). Indeed, the importance of safeguards for child victims of exploitation is necessary to redress the situation, in some countries, that children (especially girls) are held responsible for “moral offences”, when they are the victims of adult sex crimes including being held criminally responsible and subjected to harsh and inhumane treatment and punishment either in law or in practice (Santos Pais, 2015, p. 19). Lecturers may also be interested in learning about a case in which a girl was denied justice, and her family victimized, after she sought legal redress for being sexually assaulted (see SRSG on Violence against Children (2015) p. v). The full text of this case is available in this Module – entitled Case Study 7: Kainat’s Ordeal.

Children living / working on the streets

Living on the streets often results in conditions that jeopardize an individual’s safety and compromise their human dignity. Furthermore, persons who live on the streets experience increased difficulties in accessing justice and the protective functions of the law (Walsh, 2011). While living on the streets therefore impedes a child’s access to justice, those same conditions exacerbates a child’s risk of coming into conflict with the law. This creates a dynamic in which children who most need legal/statutory protection find only access to the punishing aspects of law. This is partly because children living on the streets may engage in crimes of survival, and partly because children, even those who are not living on the streets, spend increased hours in public spaces, and are therefore disproportionately impacted by public nuisance laws, anti-social behaviour orders, status offences (such as underage consumption of alcohol), or laws designed to target children (curfews and anti-association laws) (see Walsh, 2017; Squires and Stephan, 2005).

The disproportionate criminalization of children living on the streets is also due, in large part, to survival crime and child exploitation. Working together, the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UNODC, and the SRSG jointly identify that children living and/or working on the streets face increased risks of criminalization:

Children living and/or working on the streets are perceived as a social threat, stigmatized by the media and blamed for an alleged increase in juvenile delinquency.” (A/HRC/21/25 para 5).

Compounding concerns about the criminalization of children living and/or working on the streets, it is important to remember that this is often caused by children fleeing situations of violence or abuse in the home (SRSG on Violence against Children, 2013, p. 13). Such children are in particular need of child-sensitive responses that are victim and welfare oriented, rather than steeped in models of individual criminal responsibility and punishment. For example, Jamaican law allowed parents to bring their child to the court for being “uncontrollable” (Office of the Children’s Advocate, 2013). In many cases children, in particular girls, were placed in detention for lack of alternative care solutions (Caribbean Policy Research Institute and UNICEF, 2018). A local NGO reported that many of these girls had been sexually abused in the home which resulted in them missing schools or being “unruly”.

Poverty

Scholarship on the criminalization of poverty illustrates the increased risks of criminalization and/or custodial sentences for children who endure adverse socio-economic conditions (Rook and Sexsmith, 2015). These risks are particularly acute for children who endure both profound poverty and systemic discrimination, as is the case with Roma children in many parts of Europe (D’Arcy and Brodie, 2015), as well as Indigenous children, including in parts of Australia (Cunneen, 2018) and Canada (Rook and Sexsmith, 2015). In some regions, scholars and practitioners have identified that the myriad ways in which child poverty harms children requires improved data collection and analysis of the compounding contexts of adversity that result in the criminalization of children in need of care and protection (Blade et al, 2011), including through multi-dimensional analyses of poverty (for example, the multi-country study on the nexus between poverty and challenges in child protection in East Asia and the Pacific: Minujin, 2011. See also UNICEF Innocenti’s work on multi-dimensional indices of child poverty (Chzhen et al, 2017).

Status offences

Status offences are acts that would not be criminalized if they were undertaken by adults. Examples include begging, running away from home, breaching curfew, truancy, and disobedience to parents or caregivers. Laws that criminalize children for these activities constitute age-based discrimination, and contribute to the multitudinous ways in which children are needlessly brought into conflict with the law. In many instances, status offences are detected because they are activities that bring children into public spaces, and therefore to police attention. The United Nations recognizes the harmful effects of criminalizing children for status offences, as specified in the Riyadh Guidelines:

In order to prevent further stigmatization, victimization and criminalization of young persons, legislation should be enacted to ensure that any conduct not considered an offence or no penalized if committed by an adult is not considered an offence and not penalized if committed by a young person (Riyadh Guidelines, 56).

Understanding the key challenges faced by countries in promoting juvenile justice

Lack of data and statistics

A common challenge faced by many countries is the lack of data and statistics available on the situation of children in conflict with the law and, in particular, on the status of children deprived of their liberty. Measures to establish and support systems for the collection of data, disaggregated by age and sex, should be an integral part of a specialized juvenile justice response. This is foundational to the establishment of a baseline for longitudinal studies of trends with respect to the numbers of children in contact with justice systems as victims, witnesses, or as persons alleged as, accused of or recognized as having infringed the penal law. This is a pre-requisite for the development of sound policies and programmes aimed to promote effective juvenile justice and to ensure the rights of children in conflict with the law. The collection, maintenance and analysis/evaluation of these data must, however, preserve a child’s right to freedom from arbitrary interference with their privacy, and mechanisms to preserve the dignity and anonymity of children should be implemented, in accordance with the principle of the best interests of the child.

Lack of specialized juvenile justice systems

Globally, there has been a considerable shift towards the recognition of the importance of specialized child justice. It nonetheless remains the case that many countries do not have a specialized system to deal with children in conflict with the law (Liefaard, 2020). This encompasses situations in which there are no specialized legal or policy provisions relating to children in conflict with the law, as well as situations in which specialized laws may exist, but profound implementation gaps exist due to a lack of specialism within the justice sector workforce (for example – a lack of specialized courts, specialized judges, and specialized diversionary schemes). In some cases, this is because the Governments and relevant justice institutions lack capacity, lack adequate organizational and operational frameworks necessary to properly perform their duties and cooperate with each other. As a consequence, children end up being dealt with by conventional criminal justice systems that are designed by and for adults. These systems do not provide for mechanisms and institutions to enable children to benefit from diversion, alternative measures, and this often leads to an overreliance on deprivation of liberty for children in conflict with the law.

Low priority

Juvenile justice is not an issue that appears to receive priority attention by States. The problem is often exacerbated by inefficient planning to enable the most effective allocation of resources. Low priority also leads to unqualified and poorly remunerated staff dealing with children in conflict with the law and, in particular, those who are deprived of their liberty. In many countries, personnel working with children in conflict with the law especially in developing countries, lack adequate knowledge of child and youth care practices and there is little reward or prospect for advancement for those doing a good job. The selection and appointment of staff members is also haphazard, with few countries undertaking rigorous background checks and screening processes to identify qualified potential employees. These challenges can be exacerbated by failures to provide the specialized supports necessary to mitigate the vicarious trauma that justice workers often experience due to their frontline work with child victims, witnesses and children alleged as, or accused of infringing the penal law.

Lack of social reintegration programmes and services

International standards emphasize that the primary purpose of any action taken against children within the juvenile justice system, including the deprivation of liberty, must be the rehabilitation and reintegration of the child rather than punishment or the protection of society. The provision of purposeful activities in facilities where children are deprived of their liberty, such as educational and vocational training programmes, physical exercise facilities, therapy and treatment for problems such as drug addiction and mental disabilities, is lacking in many countries. To some extent this is due to a lack of resources; however, it is usually the results of inadequate recognition of the importance to promote rehabilitation and social reintegration of children in conflict with the law.

The number and profile of children in detention

While scholars have observed that punitivism, in juvenile justice, is something that ebbs and flows (there is no singular trajectory that denotes an increasingly punitive approach) (Goldson 2015; Bateman 2015) it is certainly the case that overly punitive responses can result in an increase in the number of children being drawn into the criminal justice system and being deprived of their liberty. The majority of children deprived of liberty are charged with petty crimes, are first-time offenders, and are awaiting trial. Many children belong to groups of children that should not be institutionalized (Bochenek, 2016). These include children with mental health problems, children with substance abuse problems, children living and working on the streets, children with histories of trauma, children in need of care and protection and unaccompanied foreign children (McFarlane, 2018; Gerard et al, 2018; Penal Reform International, 2014; Saar et al 2015).

It is estimated that on any given day, more than one million children are detained worldwide, against their will, in criminal justice detention, closed mental health facilities, or in immigration detention. These numbers are widely thought to significantly underestimate the extent to which children are deprived of liberty and there is crucial work to be done with respect to data collection, and the transparent monitoring of children’s trajectories through criminal justice and other closed institutions globally. Redressing gaps in the collection and retention of data, is key to ensuring that children are not “lost” or rendered invisible.

Children deprived of liberty are especially vulnerable, in many cases due to the circumstances that have precipitated their detention, (poverty, trauma, mental health issues, cognitive delay, etc) but also because physical and sexual violence, and psychological harm, are constant risks in closed institutions (Carr et al, 2016; Cashmore, 2011). Indeed, it is the closed nature of these settings that has the potential to prevent full oversight and accountability as to the treatment that children receive (O’Brien, 2020a). Independent monitoring and inspection mechanisms are important ensuring that children are treated in a manner that is consistent with their equal human dignity, and the aims of rehabilitation and reintegration (Forde and Kilkelly, 2020; United Nations, 2014). A range of international oversight and inspection mechanisms contribute to this goal, including the inspection of closed institutions by members of the Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture, where States parties have ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT).

UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty

In light of enduring gaps in knowledge about the number of children deprived of liberty, and the conditions they endure while detained, the United Nations General Assembly invited the Secretary-General to commission an in-depth Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty (A/RES/69/157, para. 52). Presented to the UN General Assembly in September 2019, the Global Study builds on the precedent of previous Global Studies, including the landmark World Report on Violence against Children (Pinheiro, 2006).

The report presented to the General Assembly describes the study as: “the first scientific attempt, on the basis of global data, to comprehend the magnitude of the situation of children deprived of liberty, its possible justifications and root causes, as well as conditions of detention and their harmful impact on the health and development of children” (A/RES/74/136, Summary).

Examples of strategies and measures to redress the overcriminalization of children and promoting effective juvenile justice systems

- The development of strong national child protection systems to ensure that children (and families) in need of support are assisted in a timely, and non-stigmatizing manner that precludes unnecessary criminal justice involvement (Santos-Pais, 2015).

- Training of professionals (including justice actors) who work with children, to ensure the exercise of professional discretion in a child’s best interests (for example, ensuring that police and judiciary are informed about children’s rights, childhood development, and the efficacy of diversion and alternatives to detention for children) (United Nations, 2014).

- Fostering close cooperation between the various sectors and institutions in charge of the provision of social welfare, education and health services to children (as well as the specially trained officers within law enforcement and victim services) (United Nations, 2014).

- Domestic incorporation of human rights law, to ensure that children’s rights are justiciable in domestic courts (for more on the various national approaches to this see, for example, Goonesekere, 2020, pp.79-80).

- The establishment and observance of a minimum age of criminal responsibility in line with the recommendations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child (O’Brien and Fitz-Gibbon, 2017; Delmage, 2013).

- The abolition of discriminatory and punitive laws as applied to children, including status offences, moral offences, mandatory sentences for children; three-strikes legislation, and laws that criminalize child victims (Santos-Pais, 2015).

- The development of a system for collecting and reporting juvenile justice data and statistics, including data and statistics on the status of children deprived of their liberty.

- The establishment of laws, procedures, authorities and institutions specifically applicable to children alleged as, accused of or recognized as having infringed the penal law (CRC, 1990, article 40(3); Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2007; 2019).

- Ensuring particular attention to the United Nations standards and norms for the treatment of children alleged as, accused of or recognized as having infringed the criminal law.

- Integrating children’s issues into their overall rule of law efforts, and developing and implementing a comprehensive child justice policy, with allocation of adequate resources, aimed at promoting and protecting the rights of children in conflict with the law.

- Promoting awareness raising campaigns and engage the media, civil society organizations, and regional and international organizations in an effort to encourage a comprehensive policy on juvenile justice that is guided by the leading principles of the CRC (United Nations, 2014).

- Ensuring that staff recruitment, training and employment policies require that all persons working with children in detention facilities and the justice system more generally, are qualified and fit to do so.

- Strict adherence to the principle that the deprivation of liberty be a measure of last resort, and for the shortest appropriate period, with alternative measures and non-custodial dispositions utilized whenever possible (CRC, 1990, article 37(b)).

- Ensuring that the primary purpose of any action taken against children within the juvenile justice system, including the deprivation of liberty, must be the rehabilitation and reintegration of the child rather than punishment or the protection of society (CRC, 1990, article 40(1)).

- The development and utilization of alternative mechanisms to formal legal proceedings (diversion) to resolve situations of children in conflict with the law; and ensuring that alternatives measures to pre-trial detention and to a sentence of deprivation of liberty- are developed, promoted and (increasingly) used (CRC, 1990, article 40(3)9b)).

- The provision of support and services for children deprived of their liberty prior and after release in order to promote their rehabilitation and reintegration into the community.

While a detailed examination of each of these strategies is beyond the scope of this Module, the following section looks at the central importance of the establishment of a minimum age of criminal responsibility as a key means of diverting children away from criminal justice involvement.

The minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR)

Building on the developmental evidence that young children lack the capacity to understand the seriousness of their wrongful actions, international law provides States with guidance on the importance of establishing a minimum age of criminal responsibility, to ensure that young children are safeguarded from the rigors of the criminal justice system.

International Law and the MACR

The importance of a minimum age below which children cannot be criminalized has been a longstanding tenet of the international normative framework on justice for children. The Beijing Rules established that States should set a MACR, and that this must not be at “too low an age level, bearing in mind the facts of emotional, mental and intellectual maturity” (1985, Rule 4).

In 1990 this was given binding legal force, with the CRC requiring that States parties establish “a minimum age below which children shall be presumed not to have the capacity to infringe the penal law” (article 3 (a)).

While the CRC does not specify the age at which this must be set, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has identified that the MACR is a core element of a comprehensive juvenile justice policy, and has provided more specific guidance in successive General Comments (General Comment No. 10 2007, para 32; General Comment No. 24 2019, para 22).

In 2007, the Committee on the Rights of the Child elaborated the following guidance, for States parties, regarding the minimum age of criminal responsibility:

a minimum age of criminal responsibility below the age of 12 years is considered by the Committee not to be internationally acceptable. States Parties are encouraged to increase their lower MACR to the age of 12 years as the absolute minimum age and to continue to increase it to a higher level (Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 10, para 32).

This same recommendation is made in the UN Model Strategies and Practical Measures on the Elimination of Violence against Children in the Field of Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (2014, para 30).

In 2019 the Committee on the Rights of the Child issued a revised General Comment on children’s rights in the child justice system (General Comment No. 24 2019). Drawing on the strength of scientific findings about adolescence as a period of rapid brain development, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has established the following expectation with respect to the MACR:

States parties are encouraged to take note of recent scientific findings, and to increase their minimum age accordingly, to at least 14 years of age. Moreover, the developmental and neuroscience evidence indicates that adolescent brains continue to mature even beyond the teenage years, affecting certain kinds of decision-making. Therefore, the Committee commends States parties that have a higher minimum age, for instance 15 or 16 years of age, and urges States parties not to reduce the minimum age of criminal responsibility under any circumstances, in accordance with article 41 of the Convention. (General Comment No. 24 2019, para 22).

Globally, the age at which children are held criminally responsible for their actions varies considerably. In some jurisdictions, the penal code provides that children can be prosecuted according to criminal law from the age of seven (for example; Mauritania; Libya; Egypt; Sudan; and North Carolina in the United States). In other countries, statute ensures that children cannot be subjected to criminal sanction until they attain the age of 16 (see, for example, in Argentina and Guinea-Bissau) and up to 18 in some countries such as Brazil. There are also many jurisdictions in which the minimum age of criminal responsibility is set somewhere in between, for example, in both Canada and the Netherlands children can be held criminally responsible from the age of 12 (Wetboek van Strafrecht (Penal Code), article 77a). There are also countries in which there is no official MACR, which means that extremely young children are at risk of being prosecuted for behaviours that are perceived to breach the penal law.

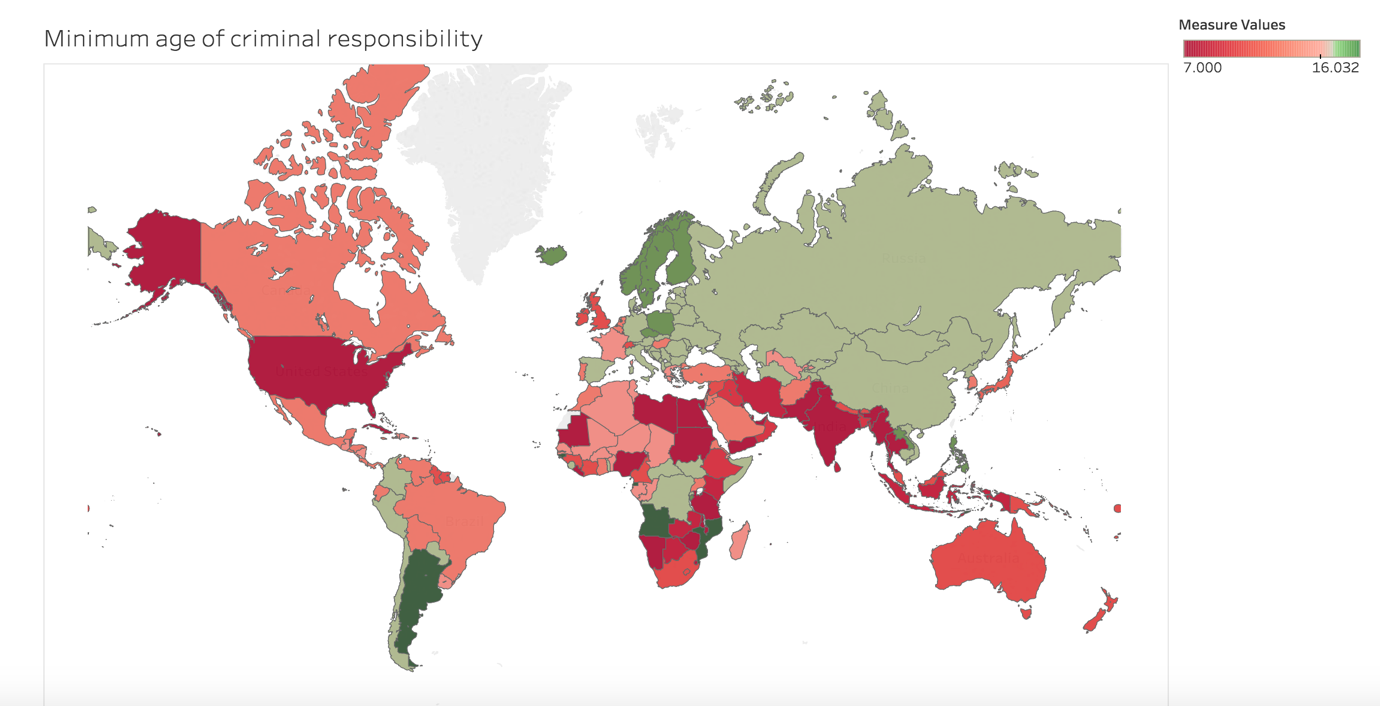

Variability of this kind means that, globally, children do not enjoy equality before the law. The map below provides an indication of the variable ages at which criminal sanctions are applied to children. The website of the Child Rights Information Network (CRIN) hosts an interactive version which includes detailed information on the MACR of each country.

Figure 2: Child Rights Information Network (CRIN). Refer to the CRIN website for an interactive version of this map, with detailed information on the MACR of each country.

Efforts to map the MACR play an important role in both monitoring and accountability; and enhancing knowledge about children’s experiences in criminal justice systems globally. Tracking the various ages at which children are criminalized also informs human rights efforts to encourage States to raise their MACR to meet international standards. Yet if raising the MACR is to remain an important pillar of child rights advocacy, it is important to recognize that, in many countries, the MACR is not as definitive as it seems. Rather, a range of factors contribute to a more complex picture for children in conflict with the law. For instance, in some countries, the age at which children are held criminally responsible varies according to sex. In other countries, the MACR, and the sanction/s applied, are contingent on whether secular, religious, or customary law is applied. In certain countries, including those in which child and forced marriage occur, married girls who come into conflict with the law are often prosecuted as adults (for a Nigerian case in which a 13-year-old married girl faced the death penalty, see: CRIN, 2014).

An additional element of complexity relates to the perceived seriousness of the crime. In many countries, the safeguards that protect very young children from the rigors of the criminal justice system do not apply if a child is accused or convicted of having committed a very serious violent offence. This is the case in Uzbekistan, for example, where the MACR is 16 years of age, except for cases of “intentional aggravated killing” in which a child can be criminalized from age 13; or from age 14 for other serious offences specified in statute (Criminal Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan (1994, amended 2002) article 17). Similarly, in Hungary the MACR is 14 except for certain serious offences, for which children can prosecuted from the age of 12, where it is proven that a child had the capacity to understand the nature and consequences of the act (Criminal Code of the Republic of Hungary, 2012, Section 16). In Belarus as part of a declared “war on drugs” Presidential Decree No. 6 passed in 2014 ‘On emergency measures for countering the illegal trafficking of drugs’ lowered the age of criminal responsibility for manufacturing and sale of drugs from 16 to fourteen. Further, in the context of the “war on drugs” in the Philippines, there has been a powerful push to lower the MACR from 15 to 12 years of age (Legaspi-Medina, 2020, p. 117). While international human rights law requires that a child’s age be taken into account in all instances in which a child is alleged as, accused of, or recognized as having breached the penal law, it remains the case that in many countries, children charged with crimes of murder, certain sex offences, or terrorism, or war crimes related offences, are often denied these safeguards, and subjected to adult criminal proceedings, including in some cases before military tribunals, and custodial sentences in adult jails. The Committee on the Rights of the Child has issued clear guidance on this issue, as follows:

The Committee strongly recommends that States parties abolish such approaches and set one standardized age below which children cannot be held responsible in criminal law, without exception. (General Comment No. 24 2019, para 25)

In addition to the perceived seriousness of offence, there are a range of discretionary mechanisms that mean that, in many countries, criminal responsibility does not necessarily adhere to a particular chronological age. For example, some francophone countries also apply the concept of “discernment” which is a similar legal concept whereby the judge defines whether the child had indeed the capacity to understand the criminal nature of his/her acts. This concept, as with many others, is a remnant of colonial French legislation which no longer exists in French juvenile justice law (Ordonnance de 1945 sur la Justice des Mineurs). Furthermore, in some common law countries, such as Australia, a MACR of ten-years-of-age may require the prosecution to prove that a child (aged between 10 and 14 years) had the capacity to know that their actions were those of serious wrongdoing, otherwise the child is presumed to be doli incapax (incapable of committing crime). While safeguards of this kind have the potential to divert very young children from the harshest forms of criminal justice punishment, it is often the case that doli incapax assessments occur once a child has already been involved in criminal justice proceedings (i.e. at the point of court appearance), so children are not necessarily spared the adverse impacts of criminal justice involvement (O’Brien and Fitz-Gibbon, 2017). A further risk with doli incapax is that children aged between 10 and 14 years can be determined capable of forming criminal intent, and prosecuted accordingly. A most concerning development with regards to doli incapax is the blanket abolition of the presumption in England and Wales – a legislative turn which now sees children criminalized from the age of ten (Goldson, 2002). In the context of this complexity, the CRC has expressed concern that “[t]he system of two minimum ages is not only confusing, but leaves much to the discretion of the court/judge and may result in discriminatory practices” (Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 10, para 30; see also General Comment No. 24 2019, para 226-27). For further on the MACR see Cipriani, 2009; Crofts, 2008; Goldson, 2013; Delmage, 2013; McDairmaid, 2013).

Next: Topic five - Realizing justice for children in the face of contemporary challenges

Next: Topic five - Realizing justice for children in the face of contemporary challenges

Back to top

Back to top