Champasack (Lao PDR), 26 March 2021 - Lao PDR continues to make headway in its fight against corruption. As of September 2020, the country completed two cycles of its United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) Review, both on criminalization/law enforcement and on prevention/asset recovery. Nevertheless, outstanding areas remain at the legal and regulatory level, including with regards to foreign bribery, private-to-private corruption and the introduction of liability of legal persons for corruption. The influx of foreign investment, the development of public-private initiatives and the implementation of mega-projects pose major corruption risks.

In order to address these challenges, Laotian authorities have expressed a number of technical capacity building needs, relating to anti-corruption and financial investigations and to the law enforcement and Anti-Money Laundering articles of the UNCAC. Stakeholders have also highlighted a need for strengthened coordination and information sharing among authorities involved in addressing corruption.

In response, UNODC held a training on anti-corruption and financial investigations, over 24-26 March 2021. The event brought together fifty-one State Inspection and Anti-Corruption Authority (SIAA) officials from 7 provinces in Lao PDR, aiming to build technical capacities nationwide, beyond the capital.

Lao officials present findings in relation to corruption case study

Areas discussed during the training include:

The role of intermediaries is key to identifying corrupt individuals

It is not uncommon for financial investigations to identify a shrinkage in transactions as bribes pass through the hands of go-betweens. The fees for those facilitating corruption can often run upwards of 30%. Typically, two forms of intermediaries are sought:

Corrupt individuals frequently enlist the help of trusted friends, relatives or colleagues. Reasons for doing so include mitigating the risk that the sum of money set aside for the purposes of bribery will be embezzled by the go-between.

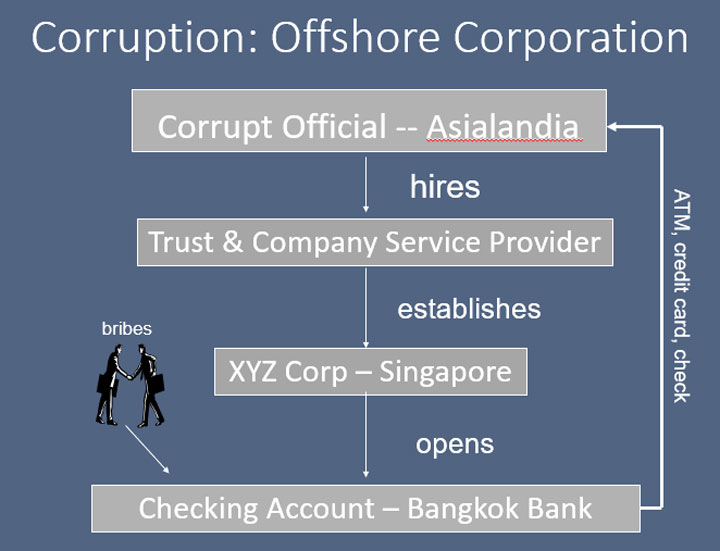

Alternatively, many seek to create a corporation in another country, in order to undermine potential investigations by Anti-Corruption Authorities. The process of doing so is often facilitated by Trust and Company Service Providers (TCSPs), typically operating from jurisdictions with lax financial regimes. To add a further layer of complexity, the corporation set up is often used to create a corporate checking account in a third country, as per the example below.

Slide by Richard Messick Showing How Offshore Corporation Seeks to Create New Layers of Complexity

Financial investigations can be progressed through online and offline channels

The starting point to find out where corrupt officials have hidden money does not need to be highly technical. To trace money, authorities can establish the presence of unexplained wealth through traditional surveillance methods, intercepted communications or even internet searches. A breakthrough might be as simple as interviewing the store owner where the spouse of a corrupt official shows to find out how the merchandise is paid for. A receipt for a credit card issued by a company may lead law enforcement authorities to seek further information from the credit card company, in order to find out where the company is registered.

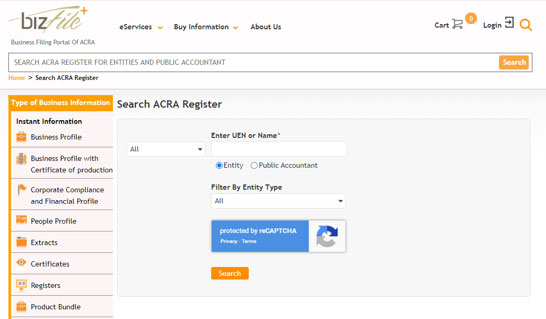

Many countries now have online systems for registering corporations (see example of Singapore, below), enabling anyone can access the registry to obtain information on a registered company. Doing so would either reveal the real, natural person who owns the corporation, or a nominee. To avoid tipping off the nominee, law enforcement authorities may prefer to proceed with a Mutual Legal Assistance request, to find out more about the link between the suspect and the corporation in question.

Slide by Richard Messick showing online system for registering corporations in Singapore, run by the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA)

The training included sessions on identifying suspects and offences, investigating legal persons and addressing corruption in infrastructure projects. The sessions included practical groupwork with reference to case studies, where trainees constructed timelines and planned responses to corruption cases.

This article is part of activities made possible with the support of the UK Government.

Other Useful Links: