(Online), 21 May 2021 - All public officials have private-capacity interests, such as outside financial holdings, family relationships and friendships, and relationships with past employers and clients. When a public official is called to participate in an official action that could affect these private interests, an actual conflict of interest situation arises. Among public officials, conflict of interest can result in corruption that undermines the credibility of government and public services.

Ensuring that a conflict of interest does not turn into corruption requires a focus on prevention, typically involving the mandatory disclosure of potential conflicts of interest by public officials and the implementation of conflict of interest management policies and procedures, in addition a series of transparency and oversight measures are necessary with regard to the establishment and management of legal persons and bank accounts.

Screenshot of Webinar on Addressing High-Level Conflict of Interest in Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, various ways to address the problem have been sought. In Indonesia, specialized 37/2012 and 30/2014 laws target conflict of interest in the public sector. Other countries have introduced relevant regulations at the administrative level, or included in codes of conduct, with administrative and disciplinary sanctions to enforce them. However, conflict of interest is a notoriously hard issue to address, as wealth is often held through proxies – typically through friends or close family members.

To build further action against this issue, UNODC held a webinar on Addressing High-Level Conflict of Interest in Southeast Asia, the latest in a series of publicly accessible events on aspects of the UNCAC. The webinar, which 561 people (215 = female) registered to attend, looked at international legal frameworks, recent cases of high-level conflict of interest in Southeast Asia and prevention approaches, including asset disclosure and beneficial ownership mechanisms.

Key issues discussed during the webinar include:

Laws against conflict of interest are essential but may need to be expanded over time

All speakers stressed the importance of introducing a specialized regulations to address conflict of interest, in line with Articles 7 and 8 of the UNCAC. Abu Kassim, Chairman of Malaysia’s National Financial Crime Centre and former Chief Commissioner of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, explained that regulatory frameworks should cover multiple elements. These include requirements around the disclosure of assets (including those held by proxies) and regulations on how conflicts of interest should be resolved (e.g. through resignation, temporary or permanent removal from the conflicting functions, divestment or restrictions).

To avoid corrupt officials adapting their behaviour to avoid penalties, laws may need to be strengthened over time. Alpha Leung, Principal Corruption Prevention Officer at Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption, identified a shift in the most prominently detected forms of corruption, from public sector bribery in the 1970s to more complex types of conflict of interest, particularly within the private sector. Likewise, Ruslan Stefanov, Programme Director for the Centre for the Study of Democracy, warned that detecting the interests of officials has become an increasingly challenging undertaking, due to the availability of overseas havens and new payment methods such as cryptocurrencies.

Given such changes to the corruption landscape, states may benefit from an effective feedback loop that enable agencies to close gaps in legal frameworks once they are identified. Drawing on the experience of Malaysia, Abu Kassim reflected on a case where it was challenging to secure the conviction of a high-level official who had avoided acting as the direct chair of a meeting in which there was nonetheless a clear conflict of interest. The incident exposed a need for an extension of the law to cover general misconduct in public office, which enabled such cases to be prosecuted going forwards.

States must be proactive in enhancing integrity to build public trust

In addition to the role of legal frameworks, multiple priorities are involved in the prevention of conflicts of interest. Other crucial elements include systems to monitor assets and transactions, data analytics-driven “red flag” mechanisms and a strong multi-stakeholder approach to oversight that includes monitoring by media and civil society groups.

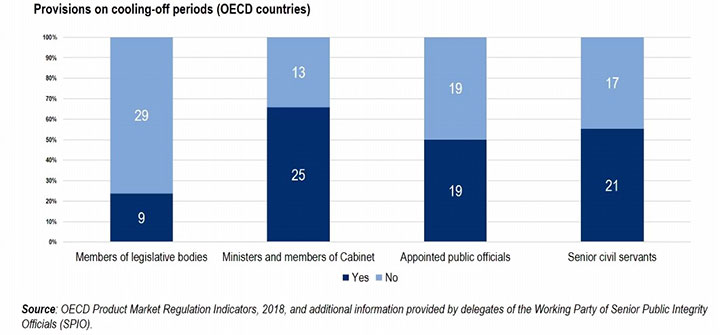

Pauline Bertrand, Policy Analyst at the Public Sector Integrity Division of the OECD, outlined a holistic approach to addressing conflict of interest. Crucially, this approach recognizes that, in terms of public trust, even the perception of an apparent conflict of interest can be damaging. She therefore called for proactivity in embedding integrity standards into legislative frameworks, and for rules that serve to build a common understanding of how conflict of interest situations can be avoided. One example of a risk area requiring clear regulation is on activities after leaving public office, to avoid what is known as the “revolving door phenomenon” (see graph below). In addition to outlining important elements of the legal framework, she also emphasized the role of awareness-raising and capacity building, to build a culture of integrity and to ensure that public officials are fully aware of how to apply regulations and avoid conflict of interest effectively.

A Strong Anti-Corruption Regime Needs Financial Transparency

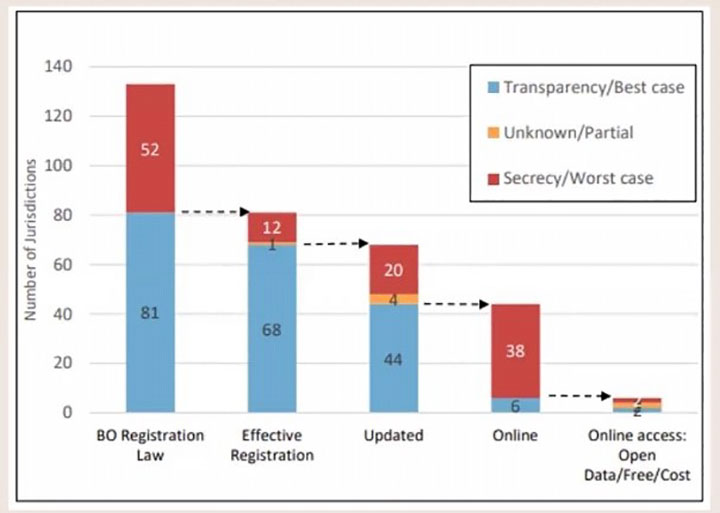

To detect conflicts of interest effectively and to prevent a culture of impunity, States require the ability to prevent corrupt officials from hiding behind secretive corporate vehicles. Moran Harari, Lead Researcher on Tax Indices at the Tax Justice Network, explained that as of April of last year, 81 countries[1] worldwide had introduced laws on beneficial ownership, which enables States to see who the true owner is of a company, trust or foundation. However, in many cases, the laws are not sufficiently robust to ensure that conflicts of interest can be detected effectively. For instance, only 44 countries require regular updates to the data held by beneficial ownership registries, while only a minority of States have so far guaranteed open access to the data online (see graph below).

Slide from Moran Harari of the Tax Justice Network summarizing loopholes in Beneficial Ownership laws

Regionally, there is likewise still much to be done to improve financial transparency. Within Asia, significant beneficial ownership legislation has been introduced in a minority of countries, namely Indonesia (for those owning at least 25% of shares), Malaysia (at least 20%) and India (under a more progressive threshold of 10%).

UNODC is working with States to promote a growing consensus around beneficial ownership and other aspects of financial transparency. A summary of a recent UNODC webinar on the state of beneficial ownership in Southeast Asia is available here.

This webinar was part of activities funded by prosperity programming of the Government of the United Kingdom and by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade of the Australian Government. Footage (where available) and written summaries of UNODC webinars are publicly available via our website.

Other Useful Links:

[1] Since April 2020, legislation on Beneficial Ownership has also been introduced by the US and Nigeria.