|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

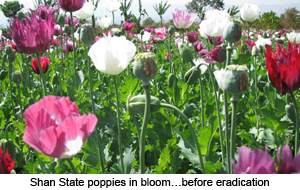

Hopong (Myanmar), 21 May 2012 - Myanmar remains the world's second largest opium poppy grower after Afghanistan, accounting for 23 per cent of opium poppy cultivation worldwide in 2011. UNODC estimates that 246,000 households are involved in opium cultivation in Myanmar, with 91 per cent of opium cultivation occurring in Shan State.

Opium poppy eradication is a priority of the Myanmar government, and recent government campaigns have seen a significant increase in the area of opium poppy destroyed. However, although serving a drug control goal, this can have disastrous consequences for poppy-farming households which are generally very poor and often in debt. Many grow poppy simply to buy food and other subsistence needs.

Opium poppy eradication is a priority of the Myanmar government, and recent government campaigns have seen a significant increase in the area of opium poppy destroyed. However, although serving a drug control goal, this can have disastrous consequences for poppy-farming households which are generally very poor and often in debt. Many grow poppy simply to buy food and other subsistence needs.

"Done without first developing alternative livelihood options, the widespread eradication of poppy can increase food insecurity as households dependent on income from now-destroyed poppy scramble to find other sources of income to feed their families," said Mr. Jason Eligh, UNODC Myanmar Country Manager.

The main drivers behind recent increases in opium poppy cultivation are chronic poverty, decreasing rural food security, and regional insecurity due to armed conflict.

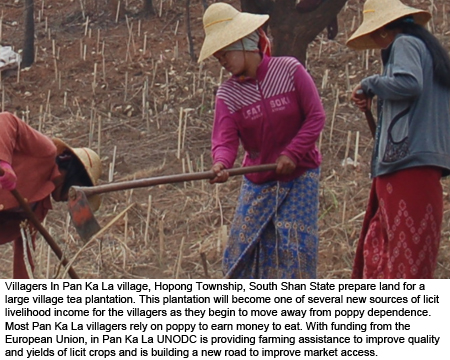

To support opium eradication efforts, in 2011 UNODC started to implement three new alternative development / sustainable livelihoods and food security projects in southern Shan State. Providing assistance directly to opium-dependent communities on the ground, these projects are funded by the European Union and the Government of Germany. They aim to reduce opium poppy production by providing alternative income-earning and livelihood opportunities. Support services include improved access to farm inputs such as seeds, seedlings, fertilizer, and tools; access to credit; improved infrastructure such as roads and waterways, as well as field irrigation; improved health service infrastructure; and, a variety of vocational training alternatives.

Currently, only a small proportion of all the Shan State villages engaged in opium poppy cultivation receive any kind of structured alternative livelihood assistance. However, the UNODC projects are a way forward that could be expanded significantly to move Shan State communities permanently away from opium dependence.

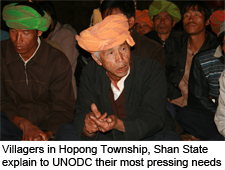

Two of the UNODC alternative development initiatives focus on 10 villages in Hopong Township in Southern Shan State; the other, in Lolien Township.

These three UNODC project interventions in Shan State involve collaboration with Myanmar government agencies including the Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control (CCDAC), local ethnic leaders and their communities, and a close partnership with sister UN agency, the World Food Programme (WFP), for emergency food assistance.

In Hopong a UNODC assessment found endemic food insecurity. Ninety-one per cent of all surveyed households were found to suffer from some level of food deficiency; 77 per cent had to borrow money just to buy enough food to eat. One quarter of all households were found to be involved in opium cultivation just so they could buy food or to pay off debts incurred previously to buy food. Similarly, in Lolien Township, a UNODC assessment found food shortages in nearly 70 per cent of sampled villages. Over 53 per cent of households were estimated to be in debt, most of which is incurred borrowing to purchase food.

The assessments revealed a pressing need for emergency food distribution to households no longer able to receive income from opium poppy cultivation. It also showed that villagers wished to grow food and cash crops and engage in income-generating activities such as raising livestock and home-based work.

To alleviate this pressing need, UNODC coordinated with WFP to distribute food as humanitarian assistance to affected communities. After food management committees determined the most food-insecure and vulnerable households, food was distributed in a close collaboration with WFP, Myanmar's CCDAC and local authorities, and the local community.

For individuals affected, the emergency food distribution is having a significant impact.

After her opium field in Hopong's Pan Tha Kwar village was destroyed in December 2011, 70-year-old Ms. Moe Bae and her son were left with no income and no rice. To survive, they cut their daily meals from three to two and borrowed one bag of rice from brokers, pledging their land as collateral.

"The bag of rice from the UN means I now worry less about food and losing my land," explains Ms. Moe Bae. "I can pay back half the rice I owe the broker, and now cook three meals a day so my son can work more hours to earn income for us."

|

|

This assistance is made possible through the kind

support of the European Union and Germany |

|