(Thailand), 18 August 2021 - Analysts of transnational organized crime find that many criminal networks operate like businesses, swayed by market forces, seeking to minimize risks and driven primarily by a profit motive. The UNODC (2019) Southeast Asia Threat Assessment finds that, in order to mitigate risks, criminal groups in the region typically recruit experienced financial managers to assist with the concealment and laundering of the proceeds of crime. Across much of the region, high levels of financial secrecy provides ample opportunities to hide illicit outflows, depriving States of funds and hindering criminal justice responses.

To address this issue in Thailand, UNODC organized a Workshop on Forensic Accounting, together with the Sanya Dharmasakti Anti-Corruption Institute of the National Anti-Corruption Commission of Thailand. The event was held online over 17-18 August 2021, for 36 anti-corruption and asset investigation officers across Thailand (20 = female).

The workshop covered theoretical and practical aspects of forensic accounting, equipping officers with the skills needed to gather evidence of corruption, fraud or money laundering hidden within financial statements. The training culminated in a major exercise using simulated financial documents, drawing on techniques learnt over the course of the workshop.

Selection of participants from UNODC Workshop on Forensic Accounting

Topics discussed during the training include:

Targeting the “financial function” of organized crime can maximize the impact of investigative resources

The continued flow of funds is fundamental to the effectiveness of most organized criminal networks. The trainer for the workshop, Mr John Chevis (Anti-Money Laundering Consultant), put forward the view that “finance is not only a critical capability but a critical vulnerability”. The UNODC Financial Disruption Methodology seeks to exploit this vulnerability, by targeting the “financial function” of criminal groups. Forensic analysis can enable law enforcement agencies to identify the weakest link within a group’s financial infrastructure, which can inform decisions as to the most resource-efficient method of disrupting its operations.

Mr Chevis gave examples of the types of disruption measures that authorities may choose to achieve the most effective and least resource-intensive impact. For instance, where an organized crime group relies on a bank for money laundering services, individual measures may range from investigations and penalties to the closure of the bank. A cost-benefit analysis might lead to the law enforcement agency leveraging the threat of reputational damage - potentially involving all the above measures – to compel the bank to replace its senior management, close customer accounts, introduce training and reject certain transactions. Focusing on the disruption of funding, rather than the prosecution of predicate crimes, can be a resource-effective way to undermine criminal operations.

Basic spreadsheets can be used to identify anomalies in financial reporting

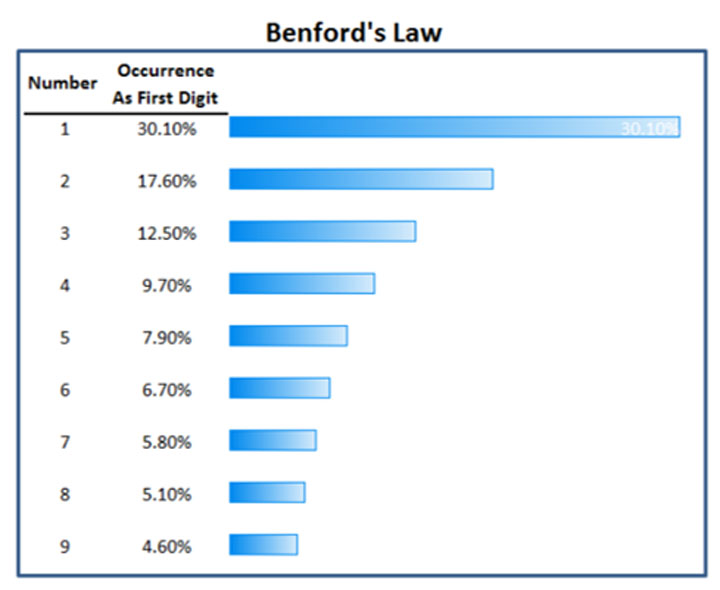

A feature of some corruption schemes is the use of fake documents, such as invoices, receipts, delivery dockets and bank statements. New technologies have increased the ease with which fake documents can be rendered, including through online fake invoice generators. The training covered a number of methods to identify fake documents, such as through the application of Benford’s Law:

Benford’s Law predicts the occurrence of digits in large sets of data, maintaining that in large datasets, some digits are likely to appear more often than others. For example, the numeral 1 should occur as the first digit in any multiple-digit number about 30.1% of the time, while the numeral 9 should occur as the first digit only 4.6% of the time.

Slide presented by John Chevis, Anti-Money Laundering Consultant, at UNODC Workshop on Forensic Accounting

During the workshop, participants learnt to apply Benford’s Law using a series of basic spreadsheet formulae, such as LEFT, COUNT and COUNTIF, and the Pivot Table function. This enabled participants to compare the percentage occurrence of each digit to the Benford percentages, to identify anomalies.

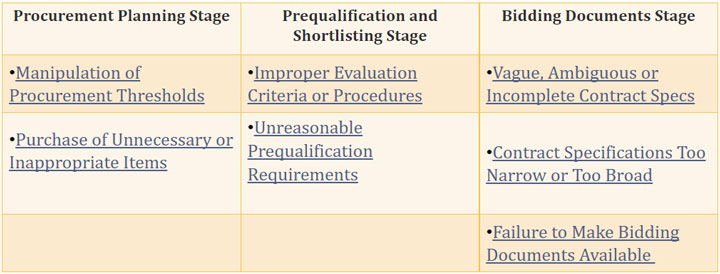

The key to uncovering corruption in procurement depends on the type of scheme involved

The effective application of forensic accounting techniques to corruption investigations requires an understanding of corruption offences themselves. In some instances, corrupt practices may exist even where irregularities in financial documentation are not readily apparent. For example, corrupt project officials may not tamper with the selection process, instead choosing what they believe to be the best bid and demanding a bribe from the selected firm before they sign a contract. In such a case, the price of the bids or proposals may rise, but the other signs of bid rigging would be largely absent.

Slide presented by John Chevis, showing some of the common bid rigging schemes at different procurement stages

During the workshop, participants noted that the key to uncovering misconduct differed according to the scheme involved. For example, corruption in the procurement process may rely on the falsification of documents (e.g. false, inflated and duplicate invoices), the misuse of the procurement process itself (e.g. split purchases or change order abuse), or the manipulation of goods or materials (e.g. product substitution). Through a detailed awareness of common corruption schemes and their associated red flags (see for instance the International Anti-Corruption Resource Center), investigating officers can draw on a broad range of evidentiary sources to disrupt corruption and fraud.

The recorded footage and a written summary of a UNODC webinar on public procurement reform is publicly available here

This webinar was part of activities funded by prosperity programming of the Government of the United Kingdom and the Government of the Republic of Korea.

Other Useful Links