Published in July 2018.

This module is a resource for lecturers

Special investigative techniques

With respect to law enforcement activities, any related covert investigation techniques are often referred to as 'special investigation techniques' (SITs). There is no universally accepted definition or list of SITs; indeed, their constantly evolving nature as the technologies used advance makes a comprehensive list elusive. In 2005, the Council of Europe adopted recommendations to member States on SITs, and in that context defined them as follows: "'Special investigation techniques' means techniques applied by the competent authorities in the context of criminal investigations for the purpose of detecting and investigating serious crimes and suspects, aiming at gathering information in such a way as not to alert the target persons." (Rec(2005)10). Significantly, and reflecting their differing priorities and role compared with intelligence agencies, a primary concern for law enforcement officials is to ensure that information gathered is admissible subsequently in court as evidence against any accused persons. Therefore, the way it is obtained must be consistent with national and international legal requirements.

While these and other investigative techniques are useful and, indeed, often necessary in combating terrorism, their very aim, i.e. to gather information about persons in such a way as not to alert the target, means that the use of SITs will normally involve an interference with the right to private life of the target and other persons. Moreover, the investigative agencies making use of SITs will commonly seek to prevent disclosure at the pre-trial and trial stages of how SITs were used in order not to disclose their methods to inter alia serious criminals such as terrorists. Though fully understandable, any resultant failure to disclose relevant information can raise questions regarding the fairness of any trial for accused persons. (See Module 11). Other human rights concerns surrounding the use of SITs can include the risk of a discriminatory use in racial, political or religious profiling practices, and the impact of covert surveillance on the fundamental freedoms of religion, thought, expression, assembly and association (see Module 13). For such reasons, the use of SITs must be carefully regulated and supervised, including judicially, to ensure that human rights are fully respected, themes which are explored further below.

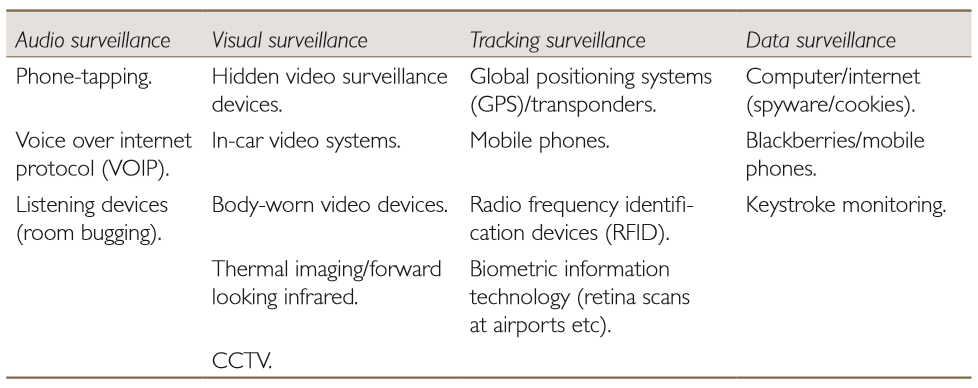

Electronic surveillance: What is it?To better understand the kind of measures involved in electronic surveillance it is helpful to break this concept down into different illustrative elements. * Source: UNODC (2009). Current practices in electronic surveillance in the investigation of serious and organized crime . New York: United Nations. Ch. 1.2, p. 2. |

The legal framework regulating surveillance measures must fulfil the requirements of sufficient clarity and precision, foreseeability as to its application, and accessibility, such that the legal framework in question is transparent and publicly accessible. Because of the constantly evolving techniques of electronic surveillance, legislators have to take particular care in crafting a legal framework that is sufficiently precise to fulfil these requirements while maintaining a degree of flexibility that ensures its ability to remain relevant as technologies evolve.

Safeguards regarding the interception of communicationsAs the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) points out, "especially where a power vested in the executive is exercised in secret", as is the case with the interception of communications, "the risks of arbitrariness are evident".* The establishment of a range of procedural safeguards to prevent the arbitrary or unlawful use of the power is therefore essential for the protection of human rights. Below is a non-exhaustive list of some of the key procedural safeguards in respect of methods of interception of communications.

The ECtHR decision in the Weber and Saravia case* provides an illustration of a very thorough examination of domestic (in this case, German) legislation regarding the interception of communications for national security purposes. ECtHR examines the extent to which the German legislation contains the above safeguards. In the end it concludes that, although the legislation provides extensive powers of secret surveillance to the authorities, the safeguards are sufficient. * Weber and Saravia v. Germany (Application no. 54934/00), Decision of 29 June 2006, European Court of Human Rights, para. 93. |

Not all electronic surveillance techniques have the same level of intrusiveness into the private sphere of individuals: a hidden video surveillance device recording a public place constitutes much less of an invasion of the private sphere of individuals than the interception of phone calls or emails. The graver the interference with legitimate expectations of privacy, the greater the need for a detailed legal framework and strong procedural safeguards and oversight.

The jurisprudence of international human rights bodies, as well as most countries' national legislation and case-law, are not entirely consistent in their interpretative approaches requiring the interception of contents of communications (whether by phone, email, or voice-over-internet-protocol, or through a listening device placed in a private premise) must be authorized by judicial order.

Other standards and safeguards on the use of SITs, including information sharing as a result of having used them, exist within other instruments too. For example, article 50(1) United Nations Convention against Corruption states that:

In order to combat corruption effectively, each State Party shall, to the extent permitted by the basic principles of its domestic legal system and in accordance with the conditions prescribed by its domestic law, take such measures as may be necessary, within its means, to allow for the appropriate use by its competent authorities of controlled delivery and, where it deems appropriate, other special investigative techniques, such as electronic or other forms of surveillance and undercover operations, within its territory, and to allow for the admissibility in court of evidence derived therefrom.

Article 50 further encourages States Parties "to conclude bilateral or multilateral agreements or arrangements for using such special investigative techniques in the context of cooperation at the international level" in relation to offences covered by this Convention (article 50(2)); or to reach decisions on a case-by-case basis to use SITs where no such agreement or arrangement exists (article 50(3)). The SITs methods envisaged include interception (article 50(4)). Other instruments make more general provision regarding the confidentiality of the "fact and substance" of a request for intelligence sharing, for instance the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (art. 2; UNSC Resolution 1617 (2005), para. 6).

Next page

Next page

Back to top

Back to top