- Extortion

- Extortion racketeering

- Loansharking

- Links between organized crime and corruption

- Bribery versus extortion

- Money-laundering

- Liability of legal persons

- Summary

- References

Published in April 2018

Regional Perspectives: Pacific Islands Region - added in November 2019

Regional Perspectives: Eastern and Southern Africa - added in April 2020

This module is a resource for lecturers

Exercises and case studies

Regional perspective: Pacific Islands RegionExercise 1 (culture and corruption=Excerpt from Tatireta and Others vs. Tong (2003)In this case, the High Court of Kiribati analysed whether local customs requiring the making of gifts could be reconciled with electoral laws prohibiting bribery and treating. The Court held that the acts denounced as bribery lacked a corrupt motive, clarifying the line between appropriate and inappropriate gift giving. "(a) Mweaka [40] Custom demands that a visitor to a maneaba (the traditional meeting house) ought to mark the visit by a cash gift called 'mweaka'. This customary payment (often discreetly made by passing an envelope containing money) appears to bear some similarity to the practice in other countries for guests to bring a bottle of wine to a dinner party or barbecue. However, one must be careful in making such comparisons; in a social environment where people have very modest resources it is important for everyone to pay his way for participation in community activities and in funding personal services. Mweaka is sometimes satisfied in kind. [41] The Elections Ordinance Pt III proscribes bribery and undue influence in connection with the election process. Section 24 describes conduct which is deemed to give rise to such an offence but the legitimacy of Mweaka has been preserved and recognised. On 29 December 1997 that section of the Ordinance was amended by adding a proviso: 'Provided further that any person making a customary offering to a Maneaba, referred to in Kiribati as "Mweaka", "Moanei" or "Ririwete", with the sole intention of showing respect for the customs and traditions of Kiribati, shall not be guilty of bribery'. [42] On 10 October 2002 s 3 of the Elections Ordinance (which contains a dictionary) was further amended by adding for the purposes of the Act the following definition: '"mweaka, moanei or ririwete" means, in accordance with Kiribati traditions and customs, the giving away or offering of a gift of a block of tobacco containing about 30 sticks of tobacco and not weighing more than 500g or its equivalent in cash of not more than $20.00 or such other higher figure as inflation may allow.'" Complete text: Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute.Excerpt from Peter Larmour (2007). Corruption and the concept of "Culture": Evidence from the Pacific Islands.

|

Case Study 1 (Mexican Drug Cartels Laundering Proceeds of Crime via Wachovia)

An investigation was started in 2005 by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) in the United States. During the course of the investigation, it was discovered that Mexican cartels were first smuggling US dollars, gained from selling illegal drugs in America, across the Mexican border and then laundering them through Wachovia Bank in the United States.

Once in Mexico, the money was given to bureaux de change ("casas de cambio") who deposited it into their Mexican bank accounts. The origin of the money was not investigated, which allowed the criminals to place their illegal earnings into the legitimate sector. These funds were then wired to Wachovia Bank's accounts in the United States and the origin, again, was not properly checked. Any remaining bank notes were shipped back to the United States using Wachovia's "bulk cash service." By using these two methods provided by Wachovia, the drug cartels were able to integrate their illegal funds into the financial system. The illicit proceeds that went through correspondent banking accounts at Wachovia were used to buy airplanes to be used in the drugs trade.

Wachovia Bank entered into an agreement with the Department of Justice to resolve the company's role in anti-competitive activity in the municipal bond investments market and agreed to pay a total of $148 million in restitution, penalties and disgorgement to federal and state agencies in 2011. Starting in 2009, the Wachovia Bank was absorbed into the Wells Fargo brand.

Case-related files

- Department of Justice (DOJ) Fact Sheet (2012).

- United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Litigation Release No. 22183 / December 8, 2011.

- United States District Court Southern District of Florida. Case No. 10-20165-CR-LENARD. 2010.

Discussion questions

- What are the stages of money-laundering in this case? How were illicit proceeds placed, layered and integrated?

- How was the Wachovia Bank involved in money-laundering? What specific charges were made?

- What is the current regulation of bureaux de change in Mexico and the United States?

- What kind of agreement was achieved between Wachovia and Department of Justice, among other relevant stakeholders? Were the charges for failure to maintain a system to detect money launderers criminal or civil? What are the differences between criminal and civil litigation in money-laundering (and other relevant) cases?

- What provisions of the Organized Crime Convention are relevant in this case?

Case Study 2 (Infiltration of Government by Organized Crime; "Mafia Capitale")

The 2017 trial in in Rome, known as the "Mafia Capitale" trial, exposed how Massimo Carminati, who was once a member of Rome's notorious far-right Magliana Gang, and Salvatore Buzzi, a convicted murderer, used kickbacks and intimidation to win city contracts and ultimately pocket millions in public funds for themselves. For years, their organized criminal group controlled key municipal services, including rubbish collection, park maintenance and refugee centres. More than 40 defendants, many of whom were former city officials associated with Carminati and Buzzi's criminal ring, were also found guilty. Among those investigated were former mayor Gianni Alemanno. Massimo Carminati and Salvatore Buzzi were sentenced to 20 and 19 years in prison respectively, after being found guilty of criminal association.

Case-related files

- Aljazeera (2015). Mafia trial puts the 'Pirate' of Rome in the dock.

- The Telegraph (2017). Italy convicts 40 in "Mafia Capital trial".

- Sentence file (in Italian).

Special features

- Criminal infiltration of governments

- Corruption in public procurement

Discussion questions

- What was the reason and the outcome of the organized crime infiltration into the Italian Government? What benefits did public officials and members of the organized criminal group received from the corrupt relationship?

- What public sectors were infiltrated by organized crime figures and what specific public interests were damaged?

Case Study 3 (Organized Crime in Viet Nam)

In 2003, the extraordinary trial of the "Năm Cam" case which involved 155 defendants - the biggest case in the history of criminal procedure in Viet Nam up to that time - shocked the Vietnamese public and seized a great deal of domestic and foreign media attention. After more than 3 months of hearings, the Ho Chi Minh City People's Court imposed the death penalty on southern mafia-style crime boss Trương Văn Cam, better known by the nickname "Năm Cam", and five of his associates (one death penalty on an accomplice was altered on appeal). "Năm Cam" was found guilty of numerous charges including murder, bribery and organizing illegal gambling. Sixteen officials, including two members of the Communist Party's powerful Central Committee and several high-ranking police officers, were punished with prison terms.

The indictment indicated that "Năm Cam" amassed a fortune during a decade at the top of an underground criminal network that consisted of gambling dens, loan sharks, protection rackets and prostitution rings. His criminal web spread from its Ho Chi Minh base to other southern provinces and the capital Hanoi, and attracted partners from Taiwan and Cambodia. It was suggested at the time of his arrest that "Năm Cam" raked in about USD 2 million per month from the protection of hundreds of restaurants, discos and illegal gambling clubs. The investigation revealed that his considerable criminal proceeds were primarily invested in several famous restaurants and discos in Ho Chi Minh City, real property, used for bribery, and transferred abroad. His legal businesses made him known as a successful businessman in Ho Chi Minh City's entertainment industry. The magnitude of his dealings made it extremely difficult for the competent authority to determine, trace and locate the illegal root of his property. Therefore, he was not convicted of money-laundering and the appeal court finally ordered to confiscate only a small part of his private property.

In 2003, "Năm Cam" was found guilty of ordering the assassination of a gangster boss, commissioning an acid attack on a rival, giving out bribes and running illegal gambling. He was sentenced to death. The trial also involved several former high-ranking officials, including a vice minister of public security, the director of the state radio and a vice national chief prosecutor.

Case-related files

- Judgment No 2114 of the Supreme Court (Appeal Court), 30/10/2003.

- Le Nguyen, Chat. (2013). The Growing Threat of Money Laundering to Vietnam: The Necessary of Intensive Countermeasures. Journal of Money Laundering Control, vol. 16(4), 321-332.

- Johnson, K. (2003), "Goodbye, Godfather".

Discussion questions

- How were extortion and corruption utilized by offenders to achieve their goals in this case?

- Were money-laundering techniques used? How?

Case Study 4 (Organized Crime Infiltration of the Police)

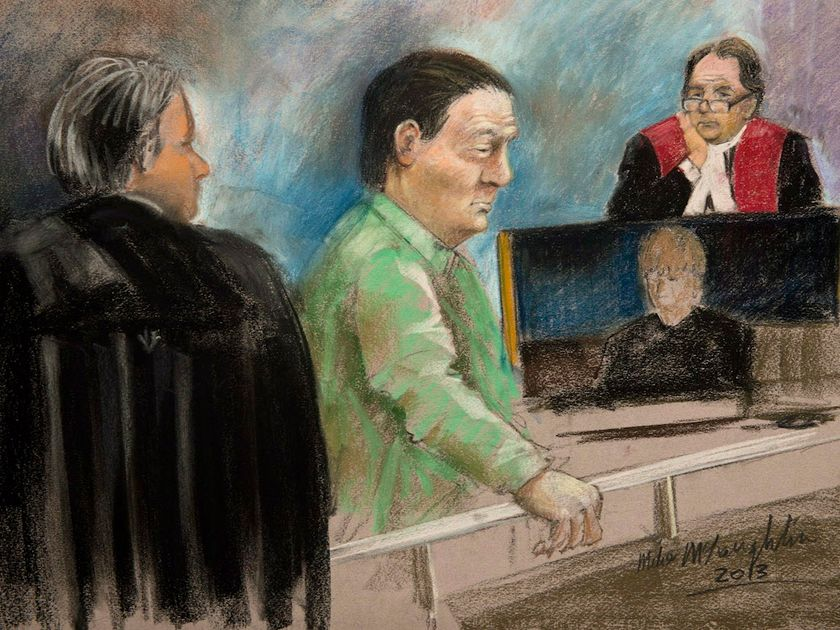

Benoît Roberge - a police officer of the Montreal Police Service, Canada - was found guilty of participation in a criminal organization under the Canadian Criminal Code, section 467.11. He had participated or contributed by act or omission to the activity of a criminal organization for the purpose of increasing the ability of the organization to facilitate or commit a crime. Considering his status of public servant at the time of the crime, he was also found guilty under section 122 of the Canadian Criminal Code, which punishes the breach of trust by public officer.

Mr. Roberge began his careers as a police officer in Montreal in 1985 and retired in 2013. From 1990, when he worked as a criminal intelligence investigator, he developed a particular expertise in the collection and analysis of criminal gang information. According to the court files, he collected sensitive information as part of his regular job duties and then sold it to René "Balloune" Charlebois, a member of the motorcycle gang "Hells Angels".

In 2004, Charlebois was found guilty of murdering a police officer and sentenced to life in prison. In 2013, he managed to escape the maximum security prison where he was detained and when the police caught up to him, he committed suicide. Nonetheless, he left secret recordings that he had made of his telephone conversations with Roberge, which were discovered by the police. Based on this information, police set up an undercover operation that culminated in the arrest and detention of Roberge.

It was discovered that Roberge informed Charlebois of the existence of two ongoing police investigations: a police investigation into drug trafficking and another targeting the Hell's Angels, including revealing information about suspects and the investigative techniques used. It was also discovered that Roberge gave information about the psychological state of a witness who was to testify in a case. In exchange for his information, Roberge received approximately $125,000, most of which (over $115,000) was recovered.

On 13 March 2014, Benoît Roberge pleaded guilty to one charge of participation in a criminal organization and one charge of breach of trust by public officer. Having served half of his seven-year sentence, the Montreal Gazette reported that he had a hearing at the Parole Board of Canada on 16 May 2017. Roberge confessed that "working constantly with criminals, especially those who led double lives as informants, caused him to live in 'a grey area' where his morals became elastic." The hearing ended with him being granted full parole.

Description: Benoît Roberge, a former high-ranking organized crime investigator, is seen in court in Montreal in 2013. Image Credit.

Case-related files

- R. c. Roberge, 2014 QCCQ 2419 (CanLII).

- Criminal Code R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46.

- Cherry, Paul. (2017). Former Montreal Cop Who Sold Information to Hells Angel Granted Full Parole. The Montreal Gazette, 17 May.

- Documentary. Benoit Roberge: Walk the Line. The Fifth Estate.

Special features

- Infiltration of police services by criminal organizations

Discussion questions

- When do organized crime groups choose to use violence and intimidation and when do they prefer to bribe law enforcement?

- Is breach of trust a serious offence? What are the consequences of organized crime infiltrating state institutions, including law enforcement agencies?

Regional perspective: Pacific Islands RegionCase Study 5 (Corruption of Public Official - Cook Islands)Teinakore Bishop was the Minister of Marine Resources and various government ministries of the Cook Islands between December 2010 and January 2014. During his tenure as Minister of Marine Resources, between October 2011 and April 2013, he issued 18 licenses for commercial purposes of fishing within the Cook Islands waters and beyond to companies associated with the Luen Thai Fishing Venture Limited, one of the largest fishing and seafood companies in the Asia-Pacific region. Luen Thai became closely connected with the government when the two entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on fishing cooperation in 2011; in such MoU, Bishop was involved in his ministerial capacity. Meanwhile, according to the evidence produced in the trial, he developed a personal connexion with the CEO of Luen Thai, Mr. Chou, a relationship not just confined to government business. In 2012, Mr. Bishop intended to acquire a resort in Aitutaki, where he lived, which would make an addition to his extensive business interest in the city. He persuaded the country's Business Trade and Investment Board that he should be the preferential buyer. To complete the sum needed for the purchase, Bishop approached Mr. Cho for a loan of USD$500,000 in January 2013, eventually obtaining the disbursement of USD$256,745 through the finance arm of Luen Thai, a company called Century Finance, in May 2013. Mr. Chou advocated on behalf of Bishop and a front man, Mr. Koteka, was used to appease Luen Thai's concerns with the loan, as its board feared a political fallout. Mr. Bishop faced the charge to have accepted or obtained a bribe from the financing arm as a reward for having issued the 18 fishing licences to Luen Thai interests. The prosecutor alleged that the bribe was in form of the loan which enabled Aitutaki Villages Limited, a company set up with Bishop's family interests and Mr Koteka as a shareholder, to complete the purchase of the resort. Further, it was alleged that Bishop knew or believed that the loan advance was received in connection with the official acts of granting the 18 fishing licenses and therefore he acted corruptly. After a 13-days trial, the jury found Bishop guilty on August 20, 2016. The sentencing stated that the integrity of the commercial fishing license regime of the country was not in jeopardy and not affected and considered that Bishop did not cultivate a friendship with Mr. Chou for taking advantage of him or his companies at some time in the future. For this and other mitigating factors, Mr. Bishop was sentenced to 2 years and 4 months of effective incarceration. Case-related files

Significant feature

Discussion questions

Case Study 6 (Money laundering by Public Officials - Fiji)The I Taukei Land Trust Board (TLTB) was established in 1940 under the iTaukei Land Trust Act (formerly known as the Native Land Trust Act) to control and administer all native lands for the benefit of itaukei landowners. Part of its duties and functions was to lease out native lands, collect the lease money and distribute it to itaukei landowners. The actual task of distributing lease money to itaukei landowners fell on the specialized "Trust Unit" (TU) of the TLTB. Between 2009 and 2012, the TU's manager (Mr. Josefa Saqanavere), together with a subordinate TU's employee (Mr. Tukana Levaci), a TLTB administration clerk (Mr. Savenaca Batibawa), and another individual (Mr. Tuimoala Raogo), tampered the TLTB computer system, wrote fraudulent checks, diverted the lease money to private bank accounts, and withdrew it for personal use. A total of $638,902.26 worth of itaukei landowners' money was stolen and laundered by the group. The money was not recovered. Except for Mr. Tukana Levaci, who fled Fiji when police investigations began, all members were charged with several counts of money laundering. They were found guilty, and each one sentenced to 13 years of imprisonment, with a non-parole period of 12 years. Case-related files

Significant feature

Discussion questions

|

Regional perspective: Eastern and Southern AfricaCase study 7 (Capital Hill Cashgate Scandal or "Cashgate" – Malawi)The so-called “Cashgate” scandal in Malawi involved the misappropriation of public money through the transfer of funds from government bank accounts to private companies, disguised as payment of goods and services. The scandal was dubbed cash gate because low level public officers who were arrested for committing the offences under this scheme were found with stockpiles of cash in their homes and vehicles. It was uncovered in September 2013, when a government accounts clerk whose monthly emoluments were less than $100 was found with huge sums of cash estimated at over $300,000.00 in his car. The assassination attempt of Malawi’s budget director followed a week later. A preliminary report developed with the assistance of the British government revealed that public officers had manipulated the payment system (integrated Financial Management Information System – IFMIS) to steal over $32 million within six months from April 2013 to September 2013. Public officers drew checks through the system in favor of private contractors on the pretext that they had supplied goods or services to the government when they had not. Once a check was issued, they would delete the transaction from the system. A full audit showed that the cash gate scandal could date back to 2009, and for the period ending 2014 the amounts involved were $356 million. Sources report that approximately one-third of the nation’s budget could have been diverted (see for instance this article published by the Financial Times). Besides the forensic audit, the Anti-Corruption Bureau and the Fiscal Police launched parallel investigations into the matter. Seventy people in both public and private sectors were arrested, among them an ex-Minister of Justice, an ex-Commander General of the Army, senior Army officials, senior Police officers, politicians, public officers, and business people. Real property and vehicles were seized and dozens of bank accounts frozen. The crime had high costs to the people of Malawi since foreign donors withdrew budgetary aid worth about 40% of the country’s annual budget (about $150 million), and the government incurred in debt, triggering high inflation and a massive increase in prices for goods and services. The scandal led to the adoption of laws allowing civil forfeitures under the Financial Crimes Act (2017), the development of plea bargain guidelines by the Director of Public Prosecutions (2014), and the procurement of new IFMIS software (2019). Case-related files

The Republic versus Osward LutepoIn the context of the “Cashgate” scandal, the High Court of Malawi convicted Mr. Osward Flywell Gideon Lutepo, upon his own guilty plea entered on 5 June 2015, on charges of conspiracy to defraud - contrary to section 323 of the Penal Code of Malawi -, and money laundering - contrary to Section 35(1)(c) of the Money Laundering, Proceeds of Serious Crime and Terrorist Financing Act. Before the “Cashgate”, he had been a successful entrepreneur with several businesses, winning contracts to supply goods to the Malawi Defence Force (MDF). In an interview under caution, he described how he came to be recruited by one Pika Manondo as an agent of some of those highly and strategically placed persons who conspired to defraud the Government of Malawi. He asserted he was made to believe that his cooperation in this criminal enterprise would serve to expedite the payment of legitimate invoices delivered to MDF. In his confession, Mr. Lutepo stated that although he was not aware of the full membership of the conspiracy, he came to know it included highly placed politicians, strategically placed senior and junior public/civil servants in many institutions, ministries, departments as well as business people. Mr. Lutepo decided to join in the conspiracy on the belief that as a consequence of the conspirators’ high and strategic positions, they would be able to pull the strings without leaving a trace and frustrate investigations by auditors and law enforcement agencies against participants in the criminal enterprise. Thus, lured into a false sense of assurance of non-detection, Mr. Lutepo dishonestly accepted to receive fraudulent cheques in favor of two of his businesses - International Procurement Services and O&G Construction Limited -, when he had in fact delivered no goods or services. To that end, he accepted that the conspirators used his businesses’ bank accounts to process the fraudulent payment of cheques and, in turn, handed over almost equivalent sums of cash. Despite having some legitimate contracts with the MDF, Mr. Lutepo or his businesses had no contracts with the Office of the President and Cabinet and Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Culture against whom most of the fraudulent cheques were drawn. As reported in the Court judgment, Mr. Lutepo confessed that: [A]fter clearance of the said cheques, I drew or caused to be drawn from my business accounts sums of cash representing the greater part of their combined face value and, for my personal benefit I used or retained a portion of the balance” (Court’s emphasis). He stated that “At the direction of the politicians, I delivered or caused to be delivered to other persons the bulk of the cash proceeds of the said cheques and retained a portion for my own personal use. So I wish to confess that I dishonestly received and retained for personal use a portion (more than 10%) of the combined face value of the said cheques. And I sincerely acknowledge that I agreed to the acquisition, possession and use of the cheques… knowing that they had been fraudulently obtained” (Court’s emphasis). Mr. Lutepo’s total fraudulent receipts and participation in fraudulent conversion amounted to MWK 4,206,337,562 (Malawian Kwacha). The proceeds of the cheques were either withdrawn as cash or otherwise disbursed. Mr. Lutepo accepted that he personally gained no less than MWK 400,000,000 as a result of the illicit transactions. The Court held Mr. Lutepo was a significant player in the “Cashgate” conspiracy. It sentenced him to eight years imprisonment for money laundering, discounting two years from the maximum penalty on account of his cooperation with the State through the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Anti-Corruption Bureau by disclosing the criminal activities and the identities of those involved, restitution efforts, and guilty plea. He received the maximum penalty of three years imprisonment for conspiracy to defraud. The terms of imprisonment were ordered to run concurrently. Case-related files

Significant features

Discussion questions

Today we are dealing with unprecedented amounts of money laundered. Tomorrow we might be confronted with a very bad and appalling case of terrorist financing. The law makers should seriously reflect on whether the punishments we have on the statute book are sufficient to address the mischief intended to be cured by the legislature through the Money Laundering, Proceeds of Serious Crime and Terrorist Financing Act.

|