This module is a resource for lecturers

Exercises

This section contains suggestions for in-class and pre-class educational exercises, while a post-class assignment for assessing student understanding of the Module is suggested in a separate section.

The exercises in this section are most appropriate for classes of up to 50 students, where students can be easily organized into small groups in which they discuss cases or conduct activities before group representatives provide feedback to the entire class. Although it is possible to have the same small group structure in large classes comprising a few hundred students, it is more challenging and the lecturer might wish to adapt facilitation techniques to ensure sufficient time for group discussions as well as providing feedback to the entire class. The easiest way to deal with the requirement for small group discussion in a large class is to ask students to discuss the issues with the four or five students sitting close to them. Given time limitations, not all groups will be able to provide feedback in each exercise. It is recommended that the lecturer makes random selections and tries to ensure that all groups get the opportunity to provide feedback at least once during the session. If time permits, the lecturer could facilitate a discussion in plenary after each group has provided feedback.

All exercises in this section are appropriate for both graduate and undergraduate students. However, as students' prior knowledge and exposure to these issues vary widely, decisions about appropriateness of exercises should be based on their educational and social context. The lecturer is encouraged to relate and connect each exercise to the key issues of the Module.

The first three exercises are surveys that could be completed as part of the class preparation process. Asking students to complete one or more of these surveys before attending the class will be helpful for illustrating some important concepts of behavioural ethics. The lecturer could capture the students' responses before the class begins. During the class, the lecturer could use data from the surveys to illustrate important concepts. Students should be able to discuss the meaning of these results, and remember them better, when they see the underlying concepts reflected in their own behaviour. An important part of behavioural ethics is the knowledge gained from behavioural science experiments. The pre-class surveys enable students to get a glimpse of how such experiments are conducted.

Each survey could take up to thirty minutes to complete. The students should answer all questions as honestly and naturally as they can. There are no right or wrong answers, so students should not waste time looking for answers on the Internet or in other external sources. They should provide their best estimates and follow their intuitions. Their responses should remain completely confidential and anonymous. The lecturer should be the only person with access to the entire data set. Any data presented in class will be of aggregated responses, not individual responses.

The surveys are followed by one in-class exercise, in which students choose and analyse their own case study of an ethical beacon.

Pre-class survey 1: Own versus others' behaviour

Lecturer guidelines

A very reliable empirical result is that people tend to be self-righteous, believing that they are more ethical than others. Recent research has revealed that this effect is nuanced, such that people tend to be especially confident that they are not as unethical as others. That is, people tend to believe that they are less likely to engage in unethical behaviour than others, and may or may not believe they are more likely to engage in ethical behaviour. This matters because people tend to underestimate how likely they are to engage in unethical behaviour, and hence underestimate the danger of ethical risks and temptations in their own lives.

You can demonstrate self-righteousness by simply having people predict how likely they are to engage in a series of moral and immoral behaviours compared to others in the class. This survey asks students to do so. Specifically, students are asked to predict how likely they are to engage in a series of 14 behaviours compared to others in the class. You can simply show to the class the average rating for each behaviour. You can also report the average rating for the seven moral behaviours and the seven immoral behaviours separately.

The questions in this survey are taken from Klein, Nadav and Nicholas Epley (2016). Maybe holier, but definitely less evil, than you: Bounded self-righteousness in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol.110, pp.660-674.

Pre-class survey 2: How much?

Lecturer guidelines

This survey asks students to indicate how much they would need to be paid for performing a number of different actions. This survey reflects the existence of five different basic moral foundations, first proposed and identified by Jonathan Haidt and his colleagues.Although much of the existing research focuses on differences across people in the importance of these five basic moral foundations, there also exists a large degree of commonality across people. Although individuals may value some foundations more than others, almost everyone recognizes the importance of each foundation. Lecturers can show this simply through this survey, as students will likely say they need to be compensated more to perform the more extreme moral violation in each of these five pairs than to perform the less extreme version. Lecturers can report the class average for each item from the survey, or simply note that the average for the second act is higher across all five moral foundations than for the first act. If that proves not to be true in the results from that particular class, then the lecturers can talk about why that might be (being sure to note issues with small sample sizes as well, if they happen to have a small class).

This survey is based on experiments described in the following publications: Haidt, Jonathan (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion.New York: Pantheon Books (see especially Chapter 7); Graham, Jesse, Jonathan Haidt and Brian A. Nosek (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 96, pp.1029-1046. An expanded explanation of this survey is provided in the 'Additional teaching tools' section of the Module.

Pre-class survey 3: Investment adviser demonstration

Lecturer guidelines

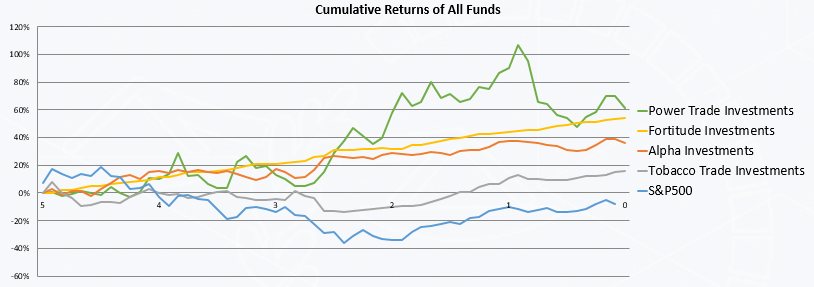

This demonstration illustrates the concept of ethical awareness by asking students to imagine that they are investment advisers who are considering four mutual funds, one of which (Fortitude Investments) is the Bernard Madoff feeder fund (the fund that was the largest Ponzi scheme in history, to date). Figure 1 shows the figure students see in the pre-class survey. S&P 500 or Standard & Poor's 500 refers to an American stock market index based on the market capitalization of 500 large companies.

Figure 1. Investment demonstration figure used in the pre-class survey.

After viewing the performance of the four funds, students are asked to indicate which fund they would advise a client to invest in. They are also asked to indicate which fund they would invest their own money in. Students are then asked to indicate how suspicious and potentially unethical each fund seems.

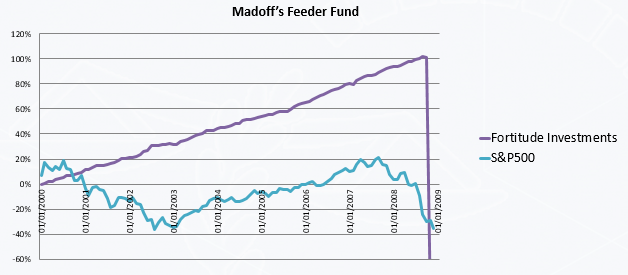

Many students (often, the majority of students), will both recommend and personally invest in Fortitude Investments (what students recommend and what they invest in personally is usually similar, and students typically switch funds due to differences in risk preferences from their presumed client rather than due to ethical considerations). This is because the returns are steady, positive, and have little volatility over the period shown in the figure from the survey. However, Fortitude Investments is also a problematic fund to invest in. The results shown in the survey are actual returns on four different funds over a five-year period (in reality, from 2000-2005). Fortitude Investments is actually the Bernie Madoff Feeder Fund, which was the largest Ponzi scheme run in human history so far. The actual returns of the Madoff fund from 2000-2009 are shown in Figure 2. The period to the left of the vertical line is what students are shown of this fund in the pre-class survey.

Figure 2. Actual performance of Fortitude Investments (The Madoff Feeder Fund) from 2000-2009, the point at which Madoff's fraud was discovered.

When Madoff was caught, many wondered why so many people invested in the Madoff fund. Part of the answer is that people behave ethically when ethics is considered at the very time a person is making a decision. If you are investing while thinking only about profits, returns, and minimizing volatility, without really thinking about ethics, then otherwise ethical people could end up providing unethical advice or investing in an unethical practice themselves. This illustrates the importance of ethical awareness when making decisions.

For this demonstration, you will want to report the percentage of your students who recommend each fund to their client, and also the percentage of those who choose to invest in it themselves. You can also report the average ratings of how suspicious and unethical the Madoff fund (Fortitude) seems. Typically, after making their investment decision, students will rate Fortitude Investments (the Madoff fund) as being less ethical than the other funds and more likely to be involved in suspicious activity, on average. You can use these ratings to point out that students are able to tell the difference between funds that look ethical and those that do not, but that that they might nevertheless choose to invest in an unethical fund simply because they were not thinking about these ethical considerations at the time they were making their investment decision.

This survey is based on the experiment discussed in Zhang, Ting, Pinar O. Fletcher, Francesca Gino and Max H. Bazerman others (2015). Reducing bounded ethicality: How to help individuals notice and avoid unethical behaviour. Organizational Dynamics, vol. 44, No. 4, pp. 310-317. An expanded explanation of this survey is provided in the 'Additional teaching tools' section of the Module.

Case study: Ethical beacon

Ask students to think of the organization or society that seems most ethical to them. This would be an organization or society that is an ethical beacon that the students might want to emulate. Ask the students to focus specifically on what the organization or society does to turn its ethical principles into daily practices, and discuss the following questions:

- What was your ethical beacon?

- How do they lead with ethical principles?

- How do they enact principles in day-to-day practices (such as hiring, evaluation, compensation, or polices)?

- How do they respond to inevitable ethical failings?

Lecturer guidelines

Too much conversation about ethics focuses on unethical behaviour. An important component of designing a more ethical life, organization, or society is to identify organizations or societies that seem to be having some success. Of course, no person, organization, or society is perfect, but some consistently behave more ethically than others. The point of this exercise is to encourage students to appreciate how ethical organizations relate to their own lives, and to articulate what an ethical organization means in their own terms. Students should feel free to select any example, but the lecturer could stimulate the students by providing some well-known examples from their region.

Next page

Next page

Back to top

Back to top