This module is a resource for lecturers

Case studies

Several case studies are provided to illustrate the different approaches to crime prevention. These can be used as handouts or included in the relevant sections of the lecture. Note that many of these case studies are considered classics - they have been instrumental in demonstrating that key approaches to crime prevention are effective. They are necessarily geographically specific. Regionally or locally relevant case studies can be constructed by viewing materials available from regional and local crime prevention entities.

Case Study 1 (Community Crime Prevention): Moonbeam Youth Training Centre (Kenya)

The Moonbeam Youth Training Centre in Mavoko, Nairobi forms part of the United Nations' Youth Empowerment Programme (YEP). The aim of the Centre is to improve the livelihood of youths living and working in slums and informal settlements through the provision of skills training and capacity building (UN-HABITAT, 2008).

The Moonbeam Training Centre aims to build low cost, sustainable housing in slum areas by training the youth in these areas in skills of alternative construction technologies. The training program equips youth with skills in employment, leadership and self-help, while also transforming informal housing structures in the slum areas into sustainable and permanent structures.

Once the youth complete the training program, they receive a certificate and have the opportunity to undertake apprenticeships in carpentry, roofing, brick manufacture, bricklaying, electrical wiring, plumbing or another related vocation.

In addition to construction industry training, the centre also provides practical training in business development and information communication technology. A combination of construction skills, complemented with business skills will better enable the youth to improve their future employment opportunities (UN-HABITAT, 2008).

UN-HABITAT (2008). Youth Empowerment Programme (YEP), Moonbeam Youth Training Centre: a ray of hope for youth living in slums . Nairobi: UN-HABITAT.

Case Study 2 (Community Crime Prevention): Stay Alive Program (Brazil)

The end of the 20 th century saw a steep rise in homicide rates in the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil and other Brazilian state capitals. Most of these homicides occurred in the slum areas of the cities, and involved young males under the age of 24.

In 2002, the Study Centre on Crime and Public Safety at the Federal University at Minas Gerais developed and piloted the Stay Alive program in the most violent slum areas of Belo Horizonte. Various community partners were brought together in the development and implementation of the crime prevention interventions. Such partners included; the Belo Horizonte City Office, State Social Defence Office, local and federal police, business organisations, NGOs and local communities.

Many of the interventions targeted youth, and included components relating to social support, education and recreation. Numerous workshops were also run, addressing issues such as violence, drugs, and sexually transmitted diseases, through programs that focused on sports, arts performance, job training, and computer skills. Additionally, crime and violence prevention training was provided to local police officers, community members, social workers, health care workers and educational staff. The military police also established a routine patrol in the slums.

A community forum was established to provide a space where community members could meet, on a monthly basis, to discuss issues such as unemployment, crime prevention, and education. This forum had the effect of facilitating community mobilisation and social cohesion.

Thirty months after the implementation of the program, there was a decrease in violent crimes in the piloted areas. Homicides decreased by 47%, attempted homicides decreased by 65% and bakery robberies decreased by 46%. Concurrently, other 'non-violent' areas in the city experienced an 11% increase in violent crime.

International Centre for the Prevention of Crime (2005). Urban crime prevention and youth at risk: compendium of promising strategies and programmes from around the world . Bangkok: International Centre for the Prevention of Crime.

Case Study 3 (Developmental Crime Prevention): Elmira Prenatal and Infancy Home Visiting by Nurses (United States)

There is now widespread recognition that a child's earliest years of life are critical for growth and development (UNICEF, 2018). Children who are brought up in loving and safe environments are able to develop essential life skills that enable them to embrace opportunities and withstand adversity (UNICEF, 2018). Programs that help and support new parents (especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds) hold great potential to positively influence a child's future and ensure beneficial outcomes for society.

The seminal Elmira prenatal and infancy home visiting program provided support to 400 young mothers who were single or from low socioeconomic backgrounds in the city of Elmira, New York. It intended to address issues of poor birth outcomes, child maltreatment, welfare dependence and other challenges associated with the mothers' compromised life course. Nurses visited young mothers on a bi-weekly basis until their child reached the age of two. The home visitation sessions were focused on providing prenatal care, baby health care and support to keep the young mothers' lives on track, by helping them find employment, plan for the future, or by linking them up with much needed services within the community.

Very positive outcomes emerged from the Elmira home visitation program. Participants in the home visitation program exhibited the following outcomes in comparison the control group (Olds et al., 1999, p. 44): improved pregnancy outcomes; better parenting skills; higher maternal employment; fewer and more widely spaced pregnancies; more mothers returned to education; less abuse and/or neglect of the children; less smoking and drinking; and by the time the children were at 15 years of age, fewer arrests and convictions (for both mother and child).

The home visitation program was also successful in delivering considerable cost savings for the government. Every $1USD spent on the home visitation program resulted in future savings of $4USD (Olds, et al., 1999, p. 56; Olds, 2002).

Olds, D. L, Henderson, C. R, Kitzman, H. J, Eckenrode, J. J, Cole, R. E, and Tatelbaum, R. C. (1999). Prenatal and infancy home visitation by nurses: recent findings. Future Child, vol. 9, No.1. p. 44-65.

Olds, David L (2002). Prenatal and Infancy Home Visiting by Nurses: From Randomized Trials to Community Replication. Prevention Science, vol. 3, No.3.

Case Study 4 (Developmental Crime Prevention): Perry Preschool Program

The Perry Preschool Program was designed to provide preschool education for young children living in poverty, and to evaluate the long-term effects of this intervention.

The Perry Preschool Program study consisted of 123 participants who resided in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and were born between 1958 and 1962. The area consisted predominantly of African American families from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Selected participants were required to be from low socioeconomic backgrounds and children had to demonstrate low intellectual performance at study entry (Schweinhart, 2013, p. 391). Participants were randomly assigned to either a treatment condition, where they would attend the Perry Preschool Program or assigned to a control condition, where they did not receive the preschool program. Participants who were assigned to the treatment condition, attended a preschool program between the ages of three and four. The preschool program consisted of daily classes of 2½ hours during the week and weekly 1½ hour home visits to each family.

Data was initially collected on the participants on an annual basis between three and 11 years of age. From then on, data collection was at 14, 15, 19, 40 and 50 years of age.

The outcomes from the Perry Preschool Program study indicated the pronounced positive effects of high-quality early education, both in the short-term and long-term. Participants who were assigned the treatment condition performed better than their control counterparts on the following indicators:

- Attained higher levels of schooling - overall 77% of treatment group graduated from high school compared to 60% of control group and 88% of women in the treatment group graduated from high school compared to 46% in control group;

- Significantly more were employed at 27 years of age (69% compared to 56%) and 40 years of age (76% compared to 62%); and

- Significantly fewer lifetime arrests for violent, property and drug crimes up to 40 years of age (but no fewer arrests for other crimes).

Using 2013 inflation figures, it was calculated that the program's return on investment amounted to $16.14USD per $1USD invested (Schweinhart, 2013, p. 396).

Schweinhart, Lawrence J (2013). Long-term follow-up of a preschool experiment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, vol.9, No.4.

Case Study 5 (Situational Crime Prevention): Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) in South Korea

A comparative analysis conducted by Ha, Oh and Park (2015) assessed the crime rates of an area that had incorporated CPTED principles into is design and an area which had not - Pangyo New Town and Yatap Town respectively. Pangyo New Town is located in Greater Seoul and was the first new development area that incorporated CPTED principles into its design from the planning stage. Yatap Town was chosen as the comparator because of its similarity to Pangyo New Town, and because it was not planned in accordance with CPTED design principles.

The Pangyo New Town Development derived CPTED principles from successful case studies from the United Kingdom, United States and Canada. The CPTED principles were then modified to suit South Korean culture. The following features were incorporated into Pangyo New Town: a gated entrance with the emblem of the complex is clearly visible; except for a few parking spaces for disabled people and emergency vehicles, all other parking is underground; an elevator is located in the car park that allows residents to directly access their homes by using a pass code or access card; well-designed pathways throughout the complex make it obvious which areas are intended for pedestrian use; trees and shrubs planted along pathway are organised and well maintained; gas pipes outside each building are covered with specially designed stainless covers in order to prevent burglars from using the pipes to climb into the first floor apartments; and clear signage, good lighting and CCTV cameras are present throughout the complex, including the underground car park.

Police data on burglary rates in Pangyo and Yatap between 2009 and 2011 were compared determine the impact of these design features. The burglary rates were significantly higher in Yatap - in 2009 and 2011, the burglary rate in Yatap was almost double that of Pangyo. In 2010, the burglary rate in Yatap was almost triple that of Pangyo - 466.19 burglaries per 100,000 population in Yatap compared to 177.02 burglaries per 100,000 population in Pangyo.

Ha, Taehoon, Oh, Gyeong-Seok, and Park, Hyeon-Ho (2015). Comparative analysis of defensible space in CPTED housing and non-CPTED housing. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, vol. 43, No.4.

Case Study 6 (Situational Crime Prevention): Social Urbanism (Medellin, Colombia)

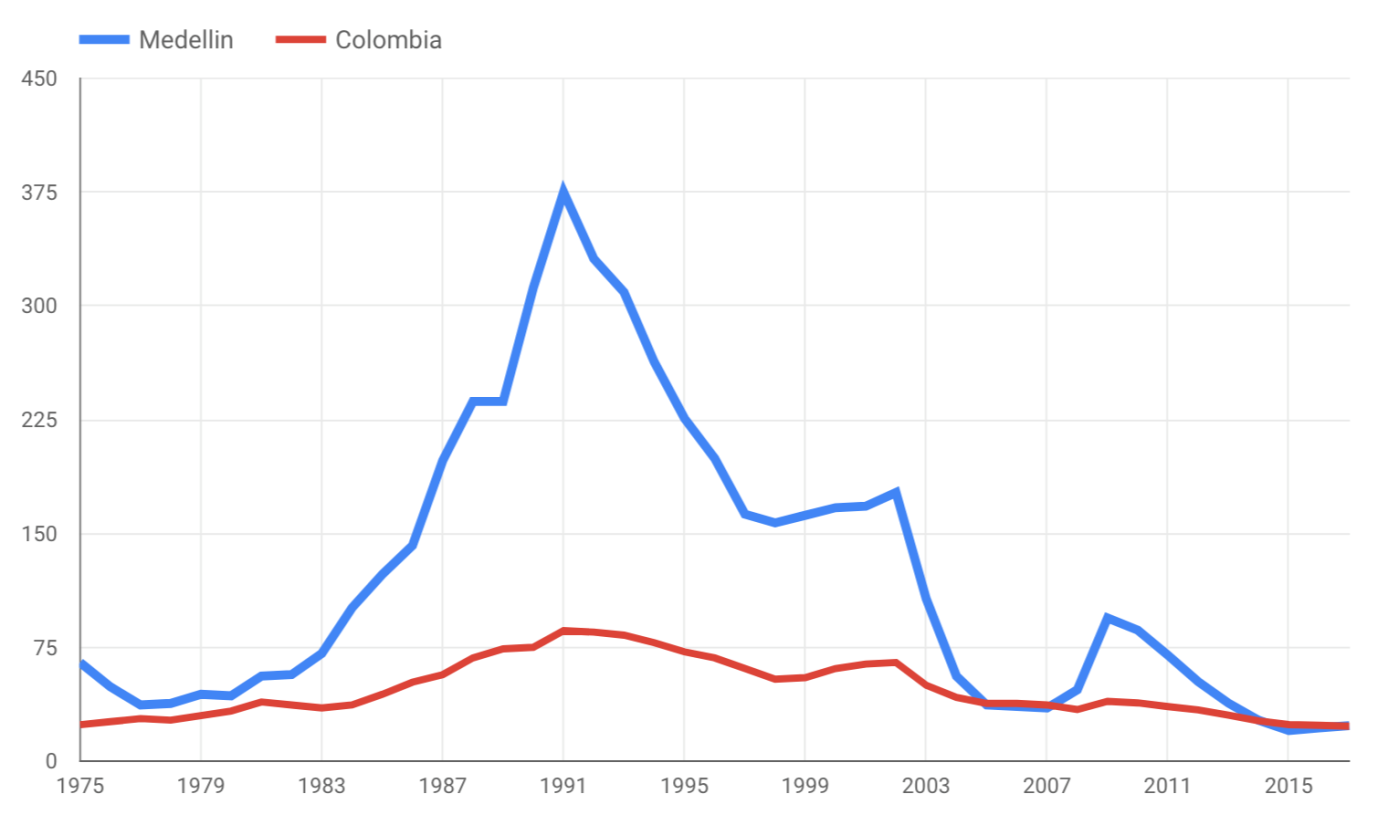

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Colombian city of Medellín was known as one of the most dangerous cities in the world. In 1991, homicide rates peaked at 375 homicides per 100,000 population (Medical Examiner's Office, 2015). This figure is more than 35 times the World Health Organisation's definition of epidemic violence (Maclean, 2015, p. 2).

The extreme levels of urban violence during this period were largely attributed to rival drug cartel gangs fighting to control the supply of illegal drugs for the export market. Violence became the way in which power and authority was gained in those areas (Maclean, 2015, p. 29). The drug cartels, gangs, urban militia and paramilitary groups gained illegitimate power by providing paid work to the many unemployed youth, as well as promising supporters upward mobility and security. In the context of high of unemployment, social insecurity, limited opportunities and limited social capital - the prospect of employment with a drug gang offered considerable appeal.

A number of regeneration policies and interventions were enacted in Medellín between the late 1990s and early 2000s. These interventions, broadly termed 'social urbanism' aimed to reduce violence by addressing social inequality and spatial exclusion, and fostering improved social cohesion within the community.

The poorest neighbourhoods of Medellín were the recipients of significant investment in urban infrastructure. In the past, neighbourhoods that were located on the outskirts of the city had been neglected, resulting in them becoming areas of high crime and social exclusion. The new policies aimed to 'change the skin of the city' (Maclean, 2015, p. 55) and the interventions included investment in mass transport systems, public spaces and iconic buildings.

One of the most widely noted interventions is the introduction of the Metrocable in 2004. The Metrocable is a cable-car transport service that connects the marginalised neighbourhoods of Medellín located on the mountainous periphery with the rest of the city. The implementation of the Metrocable enabled greater mobility between the neighbourhoods on the fringes of the city and the city centre, resulting in greater social inclusion and the ability to access more employment opportunities.

Part of the social urbanism strategy included the building of 'library parks' in the poorest areas of Medellín. 'Library parks' are public spaces that consist a library building and surrounding green space. These spaces function not only as libraries, but also as a place for educational, cultural and recreational activities to take place. Library parks will often offer a range of educational resources and training programs, which may include; computer courses and English programs. A competitive international process was utilised to select the architects to design the library parks. The significant investment, and the unique design of these library parks, signifies to the community that these areas are worth investing in and they have subsequently become landmarks of great community pride.

Other interventions implemented in Medellín include the development and improvement of public parks, football parks, public artworks, community kitchens, social housing, pedestrian bridges and the recovery of polluted streams. Additionally, $260 million USD was invested in the delivery of social programs and projects between 2004-2007. These programs provided health education, basic and secondary education, protection and assistance for vulnerable population groups, reintegration assistance for veterans, and activities for youth

The social urbanism strategy implemented in Medellín was deemed a success. Changes to the urban landscape design altered the way in which people utilise those spaces and interact with one another within them. It had the effect of creating more liveable spaces and decreasing social exclusion. Medellín has emerged as a 'model' for urban regeneration for other cities experiencing high incidences of violence.

By looking solely at crime statistics, Medellín's homicide rate in 2015 was 20 homicides per 100,000 population (Medical Examiner's Office, 2015), this represents a marked decline from the 375 homicides per 100,000 population in 1991. The graph below shows the drastic decline in homicide rates in Medellín over the past few decades.

Homicide rates per 100,000 population in Medellín and Colombia

Cerda and others (2012) compared the crime rates of neighbourhoods serviced by the Metrocable to nearby neighbourhoods with similar characteristics but were not serviced by the Metrocable. The findings revealed that between 2003 to 2008, neighbourhoods serviced by the Metrocable experienced a 66% reduction in homicide rates compared to their counterparts not serviced by the Metrocable.

Borraez (2015) compared the homicide rates in neighbourhoods before (1999-2003) and after (2004-2008) the implementation of the Metrocable. In the neighbourhoods with a Metrocable station, the homicide rate had decreased on average by 88% in 2004-2008 compared with the rate in 1999-2003. In the neighbourhoods without a Metrocable station, the homicide rate had reduced by less than 20%, some neighbourhoods even experienced an increase in homicide rates between 1999-2003 and 2004-2008.

Bea, David C (2016). Transport engineering and reduction in crime: the Medellín case. Transportation Research Procedia, vol. 18.

Magdalena Cerda and others (2012). Reducing violence by transforming neighbourhoods: a natural experiment in Medellín, Colombia. American Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 175, No. 10.

Maclean, Kate (2015). Social urbanism and the politics of violence, the Medellín miracle. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Medellín's crime statistics can be further explored on this interactive webpage.

Case Study 7 (Community Crime Prevention): Communities that Care

Communities That Care (CTC) is a community-based prevention system (Hawkins, Catalano and Arthur, 2002). CTC aims to promote the healthy development of children and young people through long term community planning to prevent health and social problems. CTC addresses the factors that facilitate the positive development of a child (protective factors) while also addressing the factors that may adversely impact the development of a child (risk factors).

CTC guides communities towards identifying and understanding local needs, setting priorities and implementing effective evidence-based interventions to address those needs. The CTC model has been implemented in numerous countries around the world and is currently operating in over 500 communities in the United States of America.

CTC is founded upon the 'Social Development Strategy', it is a strategy that promotes positive youth development by organising evidence-based protective factors into a simple strategy for action. It comprises the following components:

- Healthy beliefs and clear standards of behaviour - young people are more likely to engage in prosocial and responsible behaviour when they are surrounded by teachers, parents and a community that communicates healthy beliefs and standards

- Bonding - young people need to develop and maintain strong relationships with those who hold healthy beliefs and clear standards

- Opportunities - developmentally appropriate opportunities should be provided to young people, for active participation and meaningful interaction with prosocial others

- Skills - young people should be taught the skills they need to succeed in life

- Recognition - consistent, specific praise and recognition should be provided to young people for effort, improvement and achievement (CTC, 2018).

Results reported eight years after implementation reveal that:

- Students in CTC communities were more likely than students in control communities to have abstained from drug use, smoking cigarettes, and engaging in delinquency; and

- They were also less likely to ever have committed a violent act (CTC, 2018).

More information about CTC and their prevention programs can be found at here and here.

Case Study 8 (Community Crime Prevention): UNODC Line Up Live Up Initiative

Research shows the impact of life skills training to prevent anti-social behaviour. Sports education programmes, for example, have the potential to enhance personal and social skills and increase knowledge amongst at-risk youth. Sport holds considerable appeal for many young people and encourages their engagement. With this in mind, UNODC developed a sport-based life skills training programme called Line Up Live Up that aims to strengthen resilience of youth aged 13-18 and reduce their engagement in risky and anti-social behaviour by focusing on:

- training on key life skills (including the ability to resist negative social pressures, to cope with anxiety, and communicate effectively with peers);

- enhancing knowledge on the consequences of crime, violence and drug use; and

- young people's attitudes and how they are affected by their normative beliefs.

Line Up Live Up is a primary prevention tool that includes ten highly interactive sessions targeting different skills and knowledge areas. The programme can be run with mixed-gender groups in sport centres, schools (either as curricular or extra-curricular activities) or in other community settings. The programme requires few resources, and is therefore suitable for implementation in low resource settings. Each session includes an introduction, one or two sport activities and a debriefing session. While playing the games help youth to reach some of the learning objectives, much of the learning occurs during the debriefing phase that occurs on the sport field immediately after the exercises.

The programme was piloted in Brazil in 2017 and it will be implemented in several countries around the world in the coming years.

Case Study 9 (Criminal Justice Prevention - Problem-oriented Policing): High Speed Car Racing (Chile)

The local police in the city of Ancud in Southern Chile undertook a Problem-oriented Policing approach to resolve the problem of high-speed street races that had been taking place on public roads. Community residents had expressed concerns about safety and noise issues presented by these street races. Many of the cars used in the street races had been modified to generate excess noise. The races were not only conducted at high speed, but alcohol was often consumed as well.

The local police were able to identify that perpetrators belonged to a car club named 'Ankud Tuning'. Interviews with club members revealed that there was no other suitable location for these races to take place, hence they used public roads late at night for the races. The club is a formal and legal organisation, but it did not have any physical space to carry out its activities. Furthermore, there was a lack of recreational infrastructure or entertainment facilities in the Ancud community. The chief police officer also identified that the youth were not aware of risks associated with driving at high-speed.

The initial response was to impose heavy fines for speeding. But it did not solve the problem, as the perpetrators managed to evade the police. Races were held at secret locations and times that regularly changed.

The police then searched for an alternative place for the races, negotiating with the local air club that the races could be conducted at the airfield once a month. The local authorities, the car club, the Chilean Security Association and the air club worked together in coordinating future races.

The police also ran a series of educational events to inform youth about the risks associated with illegal high-speed races, especially in places that are not suitable for such events. A series of eight educational workshops on traffic accidents were delivered to the members of the car club.

These measures resulted in the cessation of illegal car races late at night, and a decrease in complaint calls. The air club allowed the races to take place once a month and residents of the local community were invited to spectate at these events, which gave them the opportunity to participate in more recreational activities.

Munoz, Juan (2008). Police intervention: solution to a road safety problem. Chile: Planning and Development Major Division.

Next:

Possible class structure

Next:

Possible class structure

Back to top

Back to top